Please note well: In case you were wondering, even though November is over, I will be publishing the rest of this book here, section by section. But if you can’t wait to see how it ends, you can order this book in hard copy, and the link for that is here. In addition, audio chapters are being recorded and released on the new Canon App.

The Set Up

Billy Jerome was a typical politician who looked like a statesman. He had white hair that was thick and full, and which reached almost to his shoulders. He looked like a cross between an aging hippie running a tie dye shop and a Confederate general. His jaw was square and solid, making it look like he had a lot more character going on inside than he actually did. That jaw had actually a great deal to do with his success in politics up to this point, which was considerable.

For Billy Jerome was Bryan McFetridge’s running mate. He had been picked because he had won a hard-fought Senate race in Pennsylvania, and he had done it without obviously selling his soul to the devil. And he had done it without turning the race into an acrimonious hate fest. His voting record since that election really was conservative, and he seemed like an obvious choice for McFetridge to make. He was an affable man, and he might even have become a good man eventually if only he had been allowed to do that without having to overcome many obstacles or any stiff resistance. He liked the idea of being good. McFetridge’s vetting team had found no skeletons in his closet, but this was because the one skeleton—there was only one significant one—had been carefully hidden twenty years before, and also because McFetridge’s vetting team was largely made up of evangelicals. These people were hard-working, and professional, and always on time, and were the nicest people on earth, but the last Calvinists in their respective family trees had died sometime in the mid-nineteenth century, and so their understanding of the doctrine of total depravity had died with them, meaning that their bright and cheerful descendants did not really know what questions to ask, or what a skeleton in a closet would even look like by now. So they missed it.

The oppo research team were not suffering under the same constraints of niceness, and found the problem pretty much right away. They didn’t do it in twenty minutes, but they did it pretty fast. Once that file made its way up the chain of command, this occasioned a good deal of debate on how to use the information.

The information they found, and that Billy had kept hidden in a back room for some years, for those who are interested in such things, was that twenty years before, when Billy Jerome was a lowly schlub congressman, he had a buxom staffer named Sheila that he had gotten with child. That child had been well cared for financially, as had his mom, and he was now in his second year at Yale majoring, Billy thought, in some kind of woke studies. He had no idea who his father was, and Billy guessed it was likely he would have had some sort of conniption fit if he ever found out, and thought it best that we not tell him.

His mother knew, and now Billy’s opponents in the presidential and vice-presidential showdown also knew. They did not get this information from Sheila, who had been true to her signature on the agreement, but rather from some gossipy former staffers from that by-gone era. They put two and two together, and being cynical the way Christian staffers are not, came up with four.

But what were they to do with this glorious info? This kind of thing was par for the course for a lot of politicians, but not for a guy like Billy Jerome, who had a 98% approval rating from the Family Research Council. If this glorious news came out in an opportune way for the Democrats, that could easily seal the deal on the election for them.

There had actually been a council of war on this very subject, at the highest echelons. Brock Tilton was there, naturally, as was Del Martin, and a handful of their top advisors. And the chair of the oppo team was invited in, who was delivering the file on Billy to them.

“So when do we blow this thing up?” one of the advisors said. “That seems to me to be the only question. Now or later?”

Brock Tilton shook his head sharply. “Not now. Definitely later. We use it now, we reveal it later.”

“What do you mean, boss?”

Brock swiveled in his chair and looked hard at Del. “Your debate with him is in two weeks. How are the mock debates coming? And what do you think of him as a debater? You’ve been watching all the footage, right?”

Del nodded, not liking at all the fact that he was in yet another gunk meeting. It seemed to him that they were all turning into gunk meetings. He wondered briefly why he had never noticed it before. Surely they had not magically turned into gunk meetings just within the last month. Del looked steadily back at Brock.

“He is actually quite good. Quick on his feet, and has a good mastery of facts. I do think I can stay with him, but I have to say he is good at what he does. You all know that. McFetridge picked him for a reason.”

“Then we need him to be less good on that night. We need him to take a dive. Not too obvious. Just lose a step or two. Give us a few stammering video clips to use in ads. We tell him we know, and the price of our silence is for him to help us out just a little bit in that debate.”

“You mean you don’t want to use this info?” The head of oppo gasped.

“Of course we use it, bozo,” Tilton said. “We just tell Billy that we won’t. That way he helps us out in the debate, and we get the value of the research later on, I would say about two weeks before the election would be about right. He pays for a silence he does not actually receive. We’ve been looking for our October surprise. This is it.”

Del’s stomach was churning. He was about to object, saying that to pull a double cross that way wasn’t playing it straight, when one of the advisors said it first. “But . . . to do that, after he agrees to work with us?”

“I don’t know who said it first, kid, but politics ain’t beanbag.” Del’s new conscience saw an opportunity to say something. He had to say something, and he was sick about the whole thing. “I’m not sure he would be so stupid as to agree to cooperate with us. He might not play ball, not because he is a man of integrity, but because he’s not a fool. And he is not a fool. He knows we would be holding all the cards, and could easily break our word.”

“Yep, he knows that. But even if he does the stalwart thing, the fact that he knows that we know all about it is like to put him off his game in the debate anyhow. This whole thing is a no-lose proposition.”

Brock turned to the oppo research chairman. “Good job. Tell your team good job.”

Wait… In chapter 3, wasn’t Tilton running against Mike Pence?

Yes, it was that way in an early draft. I changed it when the real election started to go south. Maybe our search and replace feature didn’t work as well as it should have.

Ah, okay. That post might have been published before the edit. Thank you!

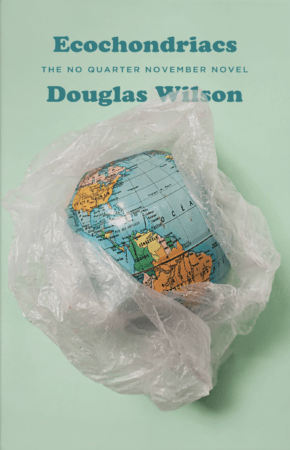

Interesting premise, Dr. Wilson, but that cover art aboslutely screams “early-eighties church bookstore midlist”. Would you like an upgrade for the second edition?