Introduction

So this is a talk about the impact a small group of Scots had on the nation of India. This is, as I take it, a subset of a larger story. The Scots were, in effect, the last European nation to be civilized, if by civilization we are referring to the cultural impact of the Christian faith working its way out into all of that nation’s institutions. At the same time, as can be seen in Arthur Herman’s fine book How the Scots Invented the Modern World, something really remarkable was happening there. This story is one aspect of that larger story.

Composition

The St. Andrews Seven, so called, was made up of one theologian and professor, Thomas Chalmers, and the six students that he inspired to give themselves over to the work of world mission, particularly to the land of India.

Thomas Chalmers was the catalyst, the spark. The men he influenced were Alexander Duff, who is probably the most famous of the six. The others were John Urquhart, John Adam, Robert Nesbit, William Sinclair Mackay, and David Ewart.

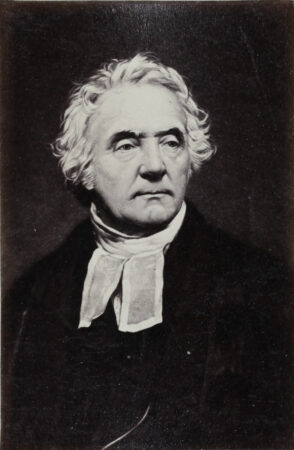

Thomas Chalmers

You may already be familiar with that name because we named our own Chalmers Hall after him. He was born in 1780 and lived until 1847. He was a great churchman, and was a leader in the Church of Scotland, and then also subsequently in the breakaway Free Church of Scotland. The issue behind that division was “intrusionism,” the idea that a minister could be intruded on a congregation without that congregation’s consent, which the Free Church faction opposed.

Chalmers was a minister, a professor of theology at St. Andrews, an educational reformer, a mathematician, an astronomer, and a political economist. He was more enthusiastic about the contributions of Thomas Malthus than he ought to have been, but we will look over that. He was a great speaker, and a best-selling author.

He was a man of great energy and passion, and that energy was really contagious. One bishop applied to him a phrase from Dante—“The holy wrestler, gentle to his own and to his enemies terrible.” His conversion was curious, in that it happened after he was educated, ordained, and serving as a parish minister in the Church of Scotland. He was a man of talents, but with no spiritual life. While serving as a minister, he was troubled concerning his own spiritual condition, a worry that sprang from a few unexpected deaths in his close family, and then a serious illness of his own. He became very aware of his spiritual need, and shortly after his 30th birthday, he came across William Wilberforce’s A Practical View of Christianity. Reading it, he encountered the gospel of Christ in stark relief for the first time, and was converted. Later he was to write on conversion in terms of the “expulsive power of a new affection.” This was certainly true in his case, and he became an evangelical dynamo.

Chalmers accepted the chair of moral philosophy at the University of St. Andrews in 1823, which is where our particular story begins. He came to St. Andrews as Scotland’s most celebrated preacher, and he promptly became a celebrated lecturer. When he taught, he did not parcel out the truth in dribs and drabs. He was a big vision speaker, and sought to impart the grand design. As Francis Schaeffer once noted, Christians tend to think in bits and pieces, instead of thinking in wholes. As Chalmers himself once put it, “Regardless of how large, your vision is too small.” He made an immediate conquest of his students, including the men we are considering. The first year at St. Andrews he was teaching Nesbit, Duff, Mackay, and Ewart. The next year was Urquhart and Adam.

The students who attended Chalmers’ lectures were set on fire with a passion for missionary work. The thing that must be noted about these men is that they were top flight students, brilliant in their work. It was not the case that they were simply punching the clock when it came to their studies, and then as pious types opted to have their off-time devoted to the support of missionary activities instead of drinking parties. No. In this, they were like the Puritans of two centuries prior. They were brains with feet. This was scholarship on fire. And they were not abstract theoreticians, but they used their minds on a very practical task before them. They knew it was necessary to do what they were talking about, and they were talking about missions.

Father or Mother or Brother . . .

One of the great obstacles that these missionaries had to overcome, and perhaps the greatest, was the love and affection of their families, who didn’t want them to go. We have to remember that the globe is a lot smaller today than it was back then. While it was possible to go back and forth between England and India, it took months. It was a far bigger deal than a 24-hour plane trek. Leaving your family for India was quite possibly leaving them for good, and sometimes “mother” didn’t adapt well to the idea.

There are some aspects to this attitude toward family that we find to be callused, and this is particularly seen in the English attitude toward their own children and the practice of putting them up in boarding schools. At the same time, we have to remember that there are verses . . .

“He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me: and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me.”Matthew 10:37 (KJV)

Nesbit provides us an example. His last visit to his family had to be extended by a few months because of his ill-health, and his parents took full advantage of the opportunity to work him over. “On the one hand his attachment to his ‘good, sweet, tender-hearted, kind, and prudent mother’ (as he described her in his diary) was deep. Yet he could not help feeling the less of her because her unrelenting opposition betrayed a lower level of faith than she professed” (The St. Andrews Seven, p. 100).

In other words, one great obstacle to the work of the foreign field was found in the domestic realm. Nevertheless, they pushed through and the impact that these men were to have on the mission field that is India was enormous.

The one corrective that I would want to offer them in this realm is not to be critical of their dedication, but rather that they were not covenantal enough in their thinking. Family and ministry are not two separate departments of your life, to be set at odds with each other, as though they were rivals. Provided he is called to the work, a family man’s ministry begins with his family and works outward from there. And if the conditions are so primitive as to preclude having a family where that is possible, then perhaps it is time to take a page from the apostle Paul and the Jesuits. Nevertheless, although we are dealing with some misplaced priorities in some of this, we are also looking at heroics.

I speak here as someone who grew up around this mentality, as my own Canadian mother was a missionary in post-war Japan, with an all-women missionary agency, and when she finally agreed to marry a persistent American naval officer, she had to overcome significant pressure to not “abandon her post.”

The Impact on India

There must have been something in the air of that century. Under the inspiration of Chalmers, these students formed the St. Andrews University Missionary Association in 1824. But they did this while unaware that the same kind of thing was happening all over the evangelical world. It was the kind of setting where students did not think they needed to wait twenty years after graduation to “have an impact.” They thought students needed to change the world while they were still students. It was one of their extracurricular activities, changing the world.

The most brilliant of these students was Urquhart, who set them all on fire with an address that he gave to their society. He himself struggled through to the personal decision that he would dedicate himself to the mission field, and with India in view. This resolve was interrupted by the providential hand of God, in that Urquhart died of what his doctor thought was a liver ailment in 1827. He was eighteen-years-old when he died. But his output up to that time had been prodigious, and his impact on his friends monumental. It was suggested that his acquaintances memorialize his work, and that task fell to one William Orme—who produced a two-volume biography . . . of an eighteen-year-old.

This left five men.

John Adam sailed for Calcutta in 1828, and then after five months of intense study, he attempted his first sermon in Bengali. He was an intense man, and died in 1831, perhaps of sunstroke. Someone, perhaps Kipling, said that only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun, and this apparently included Scotsmen. But Adam had been the same way about snow back in Scotland.

This left four. Alexander Duff had joined him in 1830, having survived two shipwrecks on the way there. While Urquhart was the most influential of the six upstream, Duff was the most influential of the five who made it to India. He founded a school in the heart of Calcutta (Scottish Church College), making the interesting decision to teach in English instead of Bengali. His strategic vision was to aim for the conversion of high-caste Hindus, in the assumption that this would have a “trickle down” effect, which it did. He also had a role in founding the University of Calcutta.

David Ewert gave himself to the task of teaching in that school, which was his post until he was taken by cholera in 1860. And Mackay was a very fine scholar, serving as the superintendent of Duff’s school during Duff’s various trips back to England. Mackay’s health was not robust, and he came close to dying numerous times. His sentiment about these brushes with death was summed up by him this way: “My chief regret was that I had done so little for Christ, and given so much of my time to the world.” His health in fragments, he retired to Scotland in 1862, dying a few years later in 1865.

Robert Nesbit gave himself to mission work in Bombay (modern Mumbai). His struggle with his mother was helpful to him when dealing with family opposition to converts coming out from Hinduism—Hindu mothers threatening suicide or striking themselves in the head with bricks. Following Christ was what mattered.

Duff left India for good in 1864, and became Professor of Missions at New College in Edinburgh. He died in 1878.

The Duff Strategy & the Challenge of Wineskins

The institutions founded and shaped by these men are still going . . . but they are now part of the establishment. And so perhaps the question might be raised, “What good was all that effort?”

I am reminded of the comment by Christopher Dawson, which was that the Christian faith lives in the light of eternity, and can afford to be patient. Part of that patience means that we must learn how to layer our metaphors. The kingdom of God does advance, inexorably, but there are different ways of thinking about it. There is the wheat field, but with all those tares in it (Matt. 13:25). There are the three measures of flour, enough to feed a regiment, and with yeast thrown in (Luke 13:21). There is a mustard seed producing a huge plant (Mark 4:31).

But for our purposes here, I would like you to think about the pattern of wineskins.

“And no man putteth new wine into old bottles: else the new wine doth burst the bottles, and the wine is spilled, and the bottles will be marred: but new wine must be put into new bottles.”Mark 2:22 (KJV)

The Lord teaches us not to be surprised at the aging of wineskins, and I believe we are also to be reminded that He is the Lord of the new wine. God is the Lord of history, and He is the one who directs the process of evangelization and missional fermentation. Because that is what it is—fermentation. He is the one who brings the new wine, which He does with regularity. It is one of His central methods.

Let’s take the death of Alexander Duff, in the year 1878. This was exactly one century before 1978, when Nancy and I had been married for three years already. And in God’s scheme of things, one century is nothing. Declaring Duff’s strategy a poor one because one wineskin got old is to complain about how God made the world. Was Paul’s strategy of planting church all over the Mediterranean a poor one because a century after he died (say, 165 A.D.), the church in Ephesus was not doing well? How about five centuries? Take the long view. The successful evangelization of the world is not going to come out of a vending machine. It is not something we are going to get from a convenience store.

The postmill view does not require us to believe that the kingdom of God takes off like a space shuttle. No, it is more like crawling on hands and knees from western Nebraska to the Continental Divide. A long time, with lots of ups and downs.

And so always remember that the meaning of history, including the history of missions, is to be grounded in eternity. Not the other way around. And we should therefore be encouraged. Your labor in the Lord, as Paul puts it in 1 Cor. 15:58, is not in vain.

Presented at the 2024 Christ Church Missions Conference

Great post!

Thank you. This has been a nagging question for a couple years now; and one that only cries louder for an answer the more history I read.