Introduction

I appreciated the fact that Scott Aniol decided to review Mere Christendom, and I would like to pursue the conversation further if I might. If we keep this up, we might actually get somewhere. Scott’s review of my book can be found here.

While our disagreements are obvious and significant, Scott clearly had read my book carefully, and quoted me in a fair-minded way. The most important indicator that this was a good faith interaction was that he didn’t allow our disagreements to force him into the bizarre position—taken by not a few of my trollversaries—of not allowing himself to agree with me on anything. All in all, this was a good review in that way.

I was also grateful that Scott kept to the issues I addressed in the book, not getting into side issues like what kind of font some Christian Nationalists used for their web statement. This was a helpful and wise move because Presbyterians and Baptists have ever and anon had historical difficulties whenever it comes to discussing issues regarding the font.

On Not Chasing Any Squirrels Here

On a subject like this one, it would be truly easy to get distracted, and spend a lot of time and energy chasing after the numerous little squirrels that are involved, when I think it would be much more fruitful to deal with the two bears that Scott identified.

And here they are:

Wilson’s Mere Christendom confirms two important ideas I have been trying to make in the current debates: (1) building Christian nations is inherently a postmillennial/paedobaptist project, and (2) forming a robust Christian public theology does not require Christian Nationalism.

Scott Aniol, A Review of Mere Christendom

If mere Christendom is doctrinally a niche project, then that would seem to undercut the mere in my mere Christendom. One of my critiques of various forms of Christendom 1.0 is that people tried to enact too much too soon, not distinguishing first order truths from third order truths.

And if we can get to what all faithful Christians want, which is a government of fallen men that does not believe itself to be divine, and we can get there without using the phrase or idea of Christian nationalism, then why wouldn’t we want to do that?

What Sort of Project?

So is the task of “building Christian nations” an inherently postmill/paedo project? I am not sure that this is a helpful way of putting it. We have been urging the establishment of a Christendom 2.0. Some of the saints are for it and some are against it, but everybody appears to agree that there certainly was once a Christendom 1.0. That actually happened in history once before, and you can think that it did in fact happen and be a credo amill, or a paedo historic premill, or whatnot. Moreover, you could also be an advocate of one of those doctrinal positions and think that life under good King Wenceslas might have been preferable to life under Klaus Schwab, in which he is telling you to shut up about whatever those doctrines are and just eat your bugs. Just because you are amill doesn’t mean you have to eat the bugs. Even if you are Calvinistic amill, and your doctrine of total depravity is so robust and gloomy that it makes you think that you probably ought to want to eat the bugs.

Now there is certainly a relationship between postmill thinking and Christian nationalism—in that at some point postmill thinking necessitates Christian nationalism, and a mere Christendom after that. This is even the case for Banner-of-Truth postmillennialists, who want the whole thing to be simply a festival of gospel preaching, and who never ever allow themselves to wonder what the magistrates over these newly-minted Christian nations were going to do with themselves when the revivals were over.

In short, Christian nationalism is kind of baked in to the postmill position, but there is nothing in the other eschatological positions that would preclude Christian nationalism. All dogs are mammals, but not all mammals are dogs. I can easily envision various situations where premills and amills are fully engaged in framing a Christian consensus that results in us repenting of our bent toward framing mischief with a law (Ps. 94:20).

Now I do admit also that some of the gloomier brethren might be a bit startled if they suddenly found themselves holding the keys to city hall. There is a place in That Hideous Strength where Ransom is complimenting MacPhee to someone on what a stalwart ally he would be in a losing fight. “But what he will do if we win, I can’t imagine.”

Because they don’t believe that any kind of victory is promised, they don’t expect it. But that doesn’t mean they couldn’t get it. I mean, setting themselves up for surprises, they say things like this:

“The biggest reason I object to Wilson’s mere Christendom proposal, however, is that we simply do not find anything like it in the New Testament. I understand the broader biblical/theological argument set forth by postmillennialists, and I do believe in the importance of systematic theology. But if God wanted us to establish nations that explicitly designate themselves as “Christian,” you would think we’d find even the slightest hint of it in the New Testament epistles.”

Scott Aniol, A Review of Mere Christendom

This is like saying that if Christ had intended for us to disciple the nations, baptizing them, and teaching them to obey everything Christ had commanded us, He would have given us a clear and unambiguous command. He would have commissioned us to a task that great. In fact, we might even have come to call it something like the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18-20).

Scott is saying here that there is not the “slightest hint” of establishing nations that are explicitly Christian in the New Testament epistles. He is saying that if our reading of the Great Commission were correct, it should show up in the epistles. Okay, I’ll bite.

“Now to him that is of power to stablish you according to my gospel, and the preaching of Jesus Christ, according to the revelation of the mystery, which was kept secret since the world began, But now is made manifest, and by the scriptures of the prophets, according to the commandment of the everlasting God, made known to all nations for the obedience of faith: To God only wise, be glory through Jesus Christ for ever. Amen.”

Romans 16:25–27 (KJV)

“And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the heathen through faith, preached before the gospel unto Abraham, saying, In thee shall all nations be blessed.”

Galatians 3:8 (KJV)

“And again, Esaias saith, There shall be a root of Jesse, and he that shall rise to reign over the Gentiles; in him shall the Gentiles trust.”

Romans 15:12 (KJV)

Not the slightest hint?

The Second Half of His First Point

But what about paedobaptism? In order to address this, I need to explain something else first.

What many modern Christians tend to do is project our modern voluntary system of church organization onto a previous era, and then try to understand the behaviors that were undeniably exhibited there (e.g. flogging Baptists) within that denominational framework. But back then when a man decided on credobaptism, and submitted to it, he was not just making a denominational statement. That act had implications for citizenship and loyalty—was it seditious? Baptism in infancy had civic ramifications, as did any challenge of it.

So, for example, when Roger Williams challenged the leaders of Massachusetts Bay, he was not just expressing a different opinion. He was doing things that imperiled the whole colony—could they have their charter revoked, could they be charged with harboring sedition, and so forth? The answer is yes. We have to remember that we are just now emerging from a situation where a lot of Christians were yelling at other Christians, for much flimsier reasons, demanding that they just comply. Just put on the mask. Just get the vaccine. And why? For the greater good, because we should love our neighbor, because Romans 13, and so on. That’s why Williams had to move to Rhode Island—for the greater good. He needed to love his neighbor by becoming somebody else’s neighbor. I jest, but there is a serious point in there.

Now someone is going to respond that this is precisely their problem with Christendom. Doctrinal issues like infant baptism should not be tied up with questions of citizenship and so forth. We need to solve that problem. I quite agree. That is one of the upgrades in Christendom 2.0. As I have argued elsewhere, this is a problem that the American settlement successfully addressed. So let’s go back to that, and make it a feature throughout all Christendom.

Bottom line: mere Christendom does not rest upon formal church establishment. It does depend upon a broad and deep Christian consensus, to which Baptists can certainly contribute. Given Baptist polity, they couldn’t be an established church. But given a certain number of Baptist churches—here’s looking at you, Alabama—they can certainly be an essential part of a Christian consensus.

Unless We Win

His second point at the top (the second bear) was that “forming a robust Christian public theology does not require Christian Nationalism.” Sure. Forming a public theology doesn’t require CN. But enacting any such public theology sure does.

It is one thing to hammer out a “robust theology of public engagement,” which can be done in a seminar room, or in a book, or in a discussion with some friends. But suppose you start to act on what you have hammered out, and because of a series of odd events, you actually win a big victory. What will you then be called?

Suppose through a series of circumstances, the unthinkable happens, and a case comes up before the Supreme Court that could possibly result in the overturning of Obergefell. Don’t laugh—there was a time when we were told that Roe was untouchable also. The Court has agreed to hear the case. Is it possible—work with me here—that the legal team seeking to challenge Obergefell could be made up of a Roman Catholic, a dispensational Baptist, and an elder in a PCA church? And if they win, what will all of them be called?

“Yet my conviction is that all of Wilson’s emphasis on Christian Faithfulness and limited government that protects free speech can be biblically defended and cheerfully pursued without his theological presuppositions or some sort of Christian Nationalism.”

Scott Aniol, A Review of Mere Christendom

Ah. But there is a difference between “biblically defended and cheerfully pursued,” which I happily grant that Scott can do just as he is, and “biblically defended and cheerfully pursued and caught.” This is a risk you run whenever you pursue anything—as the dog said when the fire truck stopped. What happens if we win?

Can a Baptist testify regarding a righteous course of action before the magistrate? Jeff Durbin does that, and he’s a Baptist. Moreover, I believe that Scott Aniol could do that also. But what Scott does not appear to be ready for is the prospect of the magistrate actually listening and repenting.

God wants all kinds of men to be saved, even kings (1 Tim. 2:1-4). And it is one thing to have a theology of pursuing the evangelism of all men, kings included, and quite another to actually evangelize all men, kings included. When you do the latter, sometimes they get converted. And when they do that, the king turns to the Baptist preacher who had so fearlessly declared the message of free grace to him, and shakes his hand, with tears in his eyes. He then says, “Brother, so glad you were sent to me. Something has been on my conscience for years now. What do I do with my prison system? There are thousands of wretches in there, some deserving, some not, and the whole thing is a convoluted mess. I am a servant of Christ now. What would He have me do?”

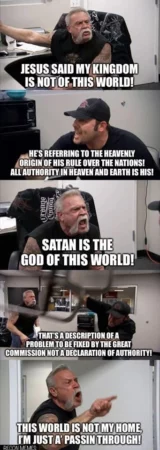

To which the evangelist replied, “Don’t know. This world is not my home.” And he departed.

Plugging the Book Yet Again

Again, I am writing about mere Christendom. If you are intrigued—and by this point, why wouldn’t you be?—then it is time for you to mosey on over, order a copy, and await developments. Excuse me. Read it and await developments.