Introduction

Despite the headline, I am not going to spend a great deal of time on Tucker’s view of the Moscow subway system, or his take on food prices over there. I will simply note that I found that whole thing embarrassingly naive, and move on to my theme, which is how cultural vindication works. But lest I be accused of leaving Tucker out in the cold, I also want to note that many of the responses to him are also in need of the same correction.

What Is Actually Being Said

When the journalist Lincoln Steffens visited Russia in 1919, and he said, “I have seen the Future, and it works,” he had not actually seen the future. What he had done was to use his own ideology as a projector, and utilizing his criticisms of his own country for a power source, he projected the whole thing onto a screen. And he did see that.

Some think Tucker Carlson is being the same kind of chump as Steffens was being. I don’t think this is actually accurate, although there is a bit of overlap. Tucker is ostensibly pointing at certain good things in Russia, but what he is actually talking about is the United States. And I would want to argue that while his points about Russia are simply ridiculous, his critical assumptions about what is happening here are on point. And I would say that Lincoln Steffens’ observations were ridiculous in both directions.

For example, someone might visit the Moscow subway and report back that—unlike on the New York subway system—they felt entirely safe. They traveled from one stop to another without ever once fearing for their lives. Yeah, the reply might come. That is because you were not handing out leaflets critical of Vladimir Putin. You were not in danger from muggers and homeless bums in Moscow, but that does not mean you were not in danger.

And everybody would consider that as a real comeback zinger, calculated to put Tucker right in his place. We would then tell him to come back home, back to the land of freedom and liberty. And so he would dutifully get on a plane to fly back to the country where the leading political rival to the sitting president is on trial in various places on charges that could make a cat laugh out loud. The intent is serious, the consequences of conviction would be serious indeed, the political bare-knuckled tactics are serious, but the charges themselves are risible and filled with helium.

The Biden DoJ really could give Putin some pointers on how to deal with political opponents. Putin’s thuggery is more naked and efficient, but Biden’s thuggery does a better job keeping up the facade of democracy. Liz Cheney recently complained about the Putin wing of the Republican Party, presumably referring to Tucker types, while ignoring the dishonest sham hearings that she was involved in, the ones with the thin veneer of legalities—legalities and niceties that looked good, like half an inch of snow on a dunghill.

But at the same time, we should not forget that the Russian equivalent of Tucker, provided he was critical of Putin, would be in a great deal of danger indeed.

If you moved the discussion on to the sanitary standards of the Moscow subway system, Tucker could just fly to San Francisco and try to walk across downtown without getting human poo on his shoes. Now granted, if he went a thousand miles east of San Francisco, he would stand a better chance of finding a working toilet than if he went a thousand miles east of Moscow. There’s always something.

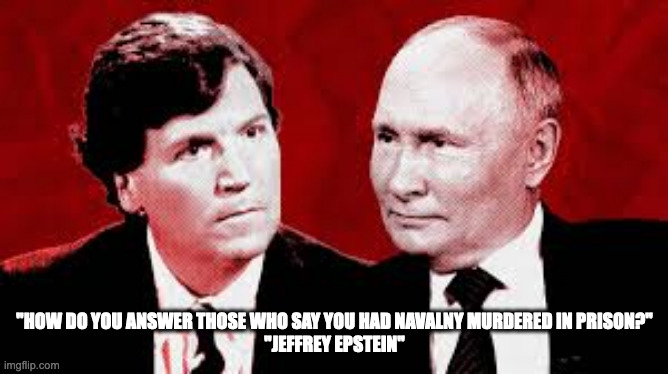

Someone will say that Alexei Navalny died in prison under really suspicious circumstances. Yeah, well, so did Jeffrey Epstein. Remember this point, for we will come back and conclude with it.

And so all this leads to the next point, which is a brief lesson on the nature of inductive and deductive reasoning.

Render General by Induction

We are covenantal creatures, and this structure is built into our very nature. This means that whenever we reason about groups of people, whether they be Americans, or Navajo, or Republicans, or Pittsburgh Steelers fans, we do so by selecting and interacting with an appointed covenantal representative.

Our selection of that representative (or set of representatives) may be just or unjust, fair or unfair, wise or stupid. The one thing it cannot be is non-existent. It is necessary for us to do this if we are going to talk about the category being represented at all. We are finite and cannot encompass the whole, and so we must select a representative, and argue that our selection was on the whole honest.

I have been to the UK a number of times, and so if you asked me what I had gathered from my visits there, I could tell you. I have also read quite a bit about British history, and so that would factor into what I would say. But if you were to compare what I had direct experience with over against what there was out there to experience, my experiences would be minuscule. The same would go for what I had read over against how much has been written. Same kind of thing.

What would matter is whether I engaged in my covenantal “naming” intelligently or not. If I ran into a couple of seven-foot guys at Heathrow, and let that shape my interpretive grid, and concluded that I had come to an island of giants, I would not be naming intelligently. If I saw bangers and mash on every menu in every restaurant I went to all over the country, and concluded that bangers and mash was a culinary “thing,” I would be well within my rights.

In other words, inductive reasoning can be wrong even when done right, in a way that deductive reasoning cannot be wrong if done right. If dogs are quadrupeds, and if Fido is a dog, then Fido is a quadruped, and there you go. That is deductive reasoning, and it is watertight. If every swan that anybody had ever seen was a white swan, we were well within our rights to assume that all swans were white—until the late 17th century, when an explorer got to Australia and found where all the black swans had been hiding.

So an inductive argument, even if strong, can still come up short.

The native tribe just south of us here in Idaho is the Nez Perce, which is French for Pierced Nose. The only difficulty with that name is that they did not actually have pierced noses. So there’s that. Perhaps the first French explorer who named them was drunk at the time. Or maybe he had run into an early Amerindian eccentric, known throughout the village for his wild and eccentric antics.

But then, on the other hand, you don’t need to drink a bottle of vinegar all the way to the bottom to determine what it tastes like. A couple of drops on the tongue should do it. An inductive argument can be indeed strong.

Potemkin Villages

At the extreme end, we have what is called the Potemkin village. Grigory Potemkin, one time lover of Empress Catherine II of Russia, wanted to impress her and/or potential allies on her visit to Crimea in the late 18th century. He had a portable village constructed such that she could sail by it on the river Dneiper. His men would be dressed like peasants, and after the empress and foreign ambassadors had sailed by, they would take the village apart and move it downstream. Now there is debate as to whether this actually happened, or if it happened in exactly this way, but regardless—we now have the useful label of Potemkin Village.

Sometimes such a village is a farce, a facade. It is entirely fictional. If someone like Tucker had been taken to a supermarket in Moscow that had produce shipped in special for his visit, that would be a Potemkin village move.

Other times it is not fictional at all, but neither is it representative. If such a visitor were taken to the one supermarket where the wives and mistresses of the oligarchs shopped, that would be an example.

And then there are even more occasions where it could be representative, but not entirely representative. We are reasoning by induction about millions of people. When you want to impress a visiting head of state do you take him to downtown Baltimore? Or to a wine and cheese event at a gallery in Manhattan?

More Than One Sink of Corruption

I saw a clip of Sen. Schumer responding to the murder of Navalny by saying that we had to respond by releasing even more aid to Ukraine. We need to fight the madman Putin, fight to the finish, sez he. But releasing more aid to Ukraine is not what would happen. What would happen is that we would release billions of dollars in aid, and we would absolutely refuse to audit where it all goes. The cover-ups for the Biden crime family have revealed to a large number of Americans that Ukraine is a sink of corruption.

A response that would have been more to the point would have been to say “in the light of the Navalny murder, we need to tend to our own corruptions first. It is time to release the Epstein client list.”

But a big mistake is lying in wait for us. The fact that Ukraine is a sink of corruption does not mean that Russia isn’t. The fact that Russia is a sink of corruption does not mean that the FBI isn’t. The whole world is under the shadow of that hideous strength.

Fifty years ago, the United States could ride around on a high horse, lecturing other nations about their electoral processes. And we would do that, too. More to the point, a lot of people would listen to us, and even take us seriously. But our high horse has since died, and all we have now is a spavined mule. And so now when we start in with the lecture, people just snort their coffee.

People like Steffens were in love with utopian ideals in their heads. People like Tucker are in love with an America that they are old enough to remember. Steffens despised a nation that was far superior to the “Future” he thought he was looking at. His assessment was based on his cotton candy ideology, and was wrong in every direction. Tucker was misled because he was looking at a city somewhere else that did not look at all like the diseased center of Portland. He was embarrassingly wrong about that Russia. He is not at all wrong about Portland.

This is why I said Steffens was wrong both coming and going. And Tucker is right about the disintegration that is happening here. It is happening as we speak, and we can see evidences of it everywhere, and in everything. And there is no answer apart from the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Nothing else will serve. Nothing else will even begin to touch it.

And so in a final word to Christian pastors. If you do not say and name the disease, if you do not preach against the disease, if you do not proclaim the deliverance from this disease as promised by the Lord Jesus, then . . . you are part of the disease.