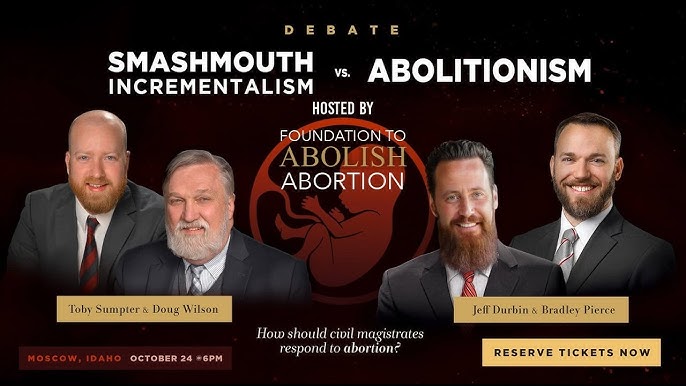

I would like to thank Jeff Durbin and Bradley Pierce for what I thought was a respectful and fruitful debate. Most of it was ex temp, but my opening statement is below.

Opening Statement

“Civil magistrates should reject regulatory Pro-Life legislative strategies as biblically forbidden, morally compromised, and practically counterproductive.”

I want to begin by thanking the organizers and sponsors of this event. This is a crucial topic and one that has arisen in a crucial time. I am grateful for the invitation to participate.

Everyone on this stage tonight agrees that the only legitimate end goal for anti-abortion activists is the outlawing of all human abortion. In this respect, we are all abolitionists. Everyone on this stage tonight is also finite, which means that this goal will not be achieved tomorrow, which means that in another sense we are all incrementalists.

But with that said, there remain some important disagreements, and our task this evening is to highlight those disagreements in a way that brings clarity to a sometimes confused and confusing debate. In this task, clarity should not be sacrificed for the sake of charity, and charity should not be sacrificed for the sake of clarity. It is a delicate balancing act, and Toby and I are grateful to Jeff and to Bradley for their labors together with us in this task.

All of us would reject the kind of incrementalism that would somehow “settle.” And by settling, I mean a posture that says “we want to restrict abortion in some way, but after that, outside those restrictions, it is all right with us if you kill the baby.” In our view, such a position is incoherent, and does not even recognize what the debate over abortion is even about.

But after that, things get murkier. This is not because the law of God is murky, or relative, but rather because it must be applied in a world that is full of shifts and evasions, and things like direction and trajectory must be taken into account. History is messy. When Solomon first began introducing the idol worship of his wives into Israel (1 Kings 11:4), there was a point when the nation was less corrupted than it was when Asa and Jehoshaphat removed many idols, but failed to remove the high places (1 Kings 15:14; 1 Kings. 22:43). Nevertheless, what Solomon was doing was far more problematic because he was leading the nation into idolatry, while Asa and Jehoshaphat were seeking to lead the nation out. Direction matters, even if it is an imperfect direction, or less than complete direction.

These were not mere denominational differences either. Solomon introduced the worship of Molech and Chemosh (1 King 11:5-7), both of which were associated with child sacrifice. We are not told this explicitly, but it is quite possible that these cultic practices were among those that the righteous kings of Judah failed to eradicate. This is not said in praise of the failure, but nevertheless six kings of Judah are commended for doing right in the eyes of the Lord—Asa, Jehoshaphat, Joash, Amaziah, Azariah, and Jotham)—while only two are commended for removing the high places also. Those men would be Hezekiah and Josiah.

The issue is not murky to God, who sees and knows all things, but because it involves the motives and intentions of the heart, we are often not in a position to judge. This is particularly the case when it comes to concrete external actions. To take one example, suppose a pro-life legislator bottles up an abolitionist bill in committee, making sure that it does not make it out to the floor for a vote. If he does this, it would be awfully hard for us to see the righteousness of his actions. At the very least, the optics are terrible. He gets pounded, right?

But let me make the issue simpler, and perhaps make our position a bit more clear. If I were a governor, and an abolitionist bill made it to my desk, I would sign it. I would do so because I would want to be a Josiah or a Hezekiah. If a heartbeat bill and an abolitionist bill both made it to my desk, I would sign the abolition bill and not the heartbeat bill. You would think that this would make me an abolitionist, but not quite. The catch appears to be in the fact that if only the heartbeat bill made it to my desk, I would sign that one also. That is where our difference lies.

And this is where the concerns about “partiality” come in. How could I, with a clear conscience, sign a bill that only protects a certain percentage of the unborn? Not only would I do it, I would do it with thanksgiving in my heart toward God. I believe that it is my responsibility to do all that is within my power to save as many lives as I can.

But here is a place where we can be thankful that God is the one who judges the thoughts and intentions of the heart. Just as it would be the work of five minutes to make the pro-life legislator look like a scoundrel, the one who smothered the abolitionist bill in committee, how hard would it be to pillory an abolitionist governor who vetoed a heartbeat bill because it “didn’t go far enough?” In fact, he would be very likely in a worse position regarding the optics because there would be children who are going to die because of his refusal to sign, who wouldn’t have died if he had signed, and the abolitionist bill bottled up in committee was never going to become a law anyhow— given the make-up of that legislature. So no actual lives were at stake. No one dies who was not already going to die, which is terrible bad, but not worse terrible bad. And this awful situation would not be helped if the governor resorted to a pocket veto.

So please note that I am not here to impugn the motives of our hypothetical governor. I don’t know his heart. But we can all see the direct effect of his actions, and make our political decisions on that basis. It would be my duty to oppose him, but not my duty at all to vilify him.

Having brought up the effect of certain actions, or the ineffectual nature of some of them, let us consider line of argument for a moment. It is often claimed that the declining numbers of abortions following the passage of something like a heartbeat bill are actually declining numbers based on smoke and mirrors. Part of this claim is stone cold fact, and part of it is a failure to realize that this stone cold fact has very little to do with the incrementalist/abolitionist debate.

The calendar year 2023 was the first full post-Dobbs year, and over a million abortions still nevertheless occurred in that year. We continue to have over a million a year, steady as she goes. This, even though we have near-total bans in around 13 states, and various restrictions in others. In the near-total-ban states, abortions really have plummeted to near zero, but the national average for abortions has not plummeted. And so while some states have been gratified to see abortion clinics shutting down, other states are what might be called “surge states.” States like Illinois have been opening up new clinics to accommodate the traffic from out of state.

And so abolitionist critics are quite right that we have not solved our nation’s bloodguilt, not even close. But this cannot be a practical argument against the near-total ban approach because we would be in exactly the same boat if 4 of those 13 states were total ban, abolitionist states, and not near total-ban states. Someone can drive to Illinois from a near-total ban state, and they can also drive to Illinois from a total-ban state.

I would mention here as an aside—albeit a very important aside—the fact that this dismaying reality illustrates how the solution to America’s spiritual leprosy is not a political solution. Our only hope of averting the judgment of God is a massive reformation and revival.

Nevertheless, until God grants that great movement of the Spirit, we are still here, and we still have political responsibilities. We still have the responsibility to find out what the biblical approach is, and then to go do that, as best as we are able.

And so I would like to complete my argument by applying an observation made by the great Thomas Sowell. He said that the liberal thinks in terms of solutions, while the conservative thinks in terms of trade-offs. The liberal sees a problem, and wants to spend money on a solution. The conservative knows that the money spent on that solution will not be available elsewhere to do something else. He sees the trade-off.

Now apply this principle to the “practically counterproductive” aspect of this debate. To introduce an abolition bill in one state is to be a geographical incrementalist. If you introduced the bill in the Idaho legislature, this is not a declaration that you don’t care about the unborn in Oregon. In the same way, to introduce a heartbeat bill is not to say that you don’t care about the children who do not yet have a heartbeat. You are just doing what you can—and you can’t do anything in Oregon because you don’t live there and you don’t have a vote. And you can’t do anything about the children who do not yet have a heartbeat because you don’t have the votes.

The whole thing is terrible, but what are we going to do? The answer should be to do what we can.

A consistent totalist approach would have to find a state where this could happen, and then: ban all abortions, secede from the Union, and set up robust border security to keep your pregnant women from traveling to Illinois. I mean, how is it a consistent abolitionist position to ban all abortions in your state while remaining a state of peace with the state next door, which allows abortions through the third trimester? This would indeed be one of Sowell’s trade-offs—because trade-offs are a fact of life—and so the difference between people is that some acknowledge the trade-offs they are making in pursuit of their goal, while for others the trade-offs must go unacknowledged.

I have no doubt that these points and others will be opened up and unpacked in the discussion to follow. Please pray for us all as we labor together to close on the truth.