Introduction

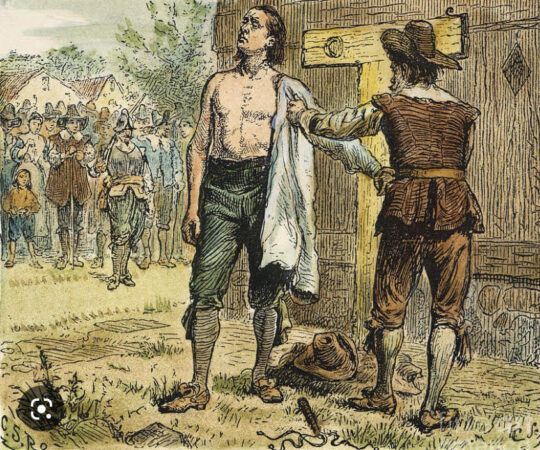

So yes, there was an incident in colonial Virginia when the authorities had a Baptist minister flogged, and he was flogged because of his Baptist convictions. This happened much to the dismay of Patrick Henry, not a Baptist at all, but a true lover of religious liberty. Henry was a lifelong Anglican communicant—although when he was a boy, his mother would take him to hear the great Presbyterian minister Samuel Davies, who had an enormous impact on him. Patrick Henry had a true ecumenical spirit, which was directly related to his love of religious liberty. It is not surprising that he was appalled that Virginia would flog a Baptist minister. We all are appalled as well. Can I get an amen?

So why would I bring this up?

A Little Thought Experiment for You

If I am laboring to get people to think happy thoughts about a restored Christendom, which is what my mere Christendom project amounts to, then why on earth would I remind everybody that back in the good old Christendom-times we used to flog Baptists? Baptists have historically been all about the separation of church and state—and I trust you can see why—and many of them are still spooked by the idea of any kind of Christendom. Some of them are kind of skittish about it. That jumpiness is kind of in their DNA. When you bring up the subject of the Christian prince with them, you can see their left eye start to twitch.

So we all know what we think about flogging Baptist ministers. We all disapprove of it, right? We think it is a bad deal and not to be done. Glad we all agree. But here is where my thought experiment comes in, and I freely acknowledge beforehand that it contains a little trap for you. You have been fairly warned. You may continue to read, but you need to be wary. Here is the question:

What did Jesus Christ think of it?

There are only three options. He either approves of it, or He disapproves of it, or He doesn’t care one way or the other. Got that? Christ either approves, disapproves, or is apathetic about the question.

Now if the Lord approves of flogging Baptists, then we as Christians would have to rethink our opposition to it. We would also have to rethink a lot of other stuff besides . . . I mean, right? Good thing that is not very likely. So let’s move on to another option. If the Lord doesn’t care one way or the other, then why should we care one way or the other? Still with me? If the Lord approves, then so should we. If the Lord doesn’t care, then we have the liberty to not care either.

Some of you by this point are itching to tell me to quit fooling around with such nonsensical options. Of course Jesus Christ disapproves of flogging Baptist ministers. Okay, then . . . welcome to mere Christendom, friend. You are telling me that the magistrates of Virginia and Massachusetts had an obligation to bring their behavior into conformity with what Christ would approve. How does it feel being a Christian nationalist now?

The problem with the magistrates flogging the Baptist is not that they were doing the will of God. They thought they were, but they were not. The problem was not that they were doing the will of God, the problem was that they were not doing the will of God.

This obviously means that in any renewed Christendom we should be redoubling our efforts to ascertain what God would actually have us do. I am advocating Christendom 2.0, which assumes that Christendom 1.0 had some bugs in it that needed to be fixed. And so when we ascertain what God actually expects from us . . . here’s a radical thought . . . we should try to do it. We should do what He wants instead of doing (in His name) what He does not want. I am advocating obedience to God, not disobedience to God.

And for the life of me, I cannot figure out how my argument that the Christian magistrate should not use the law in order to sin is somehow refuted by pointing to Christian magistrates who used the law to sin. I feel like some of us are talking past each other.

Now somebody else is going to object, refusing to acknowledge my three options, and he will say that we should simply oppose such outrages in our own name, on our own authority. To which the demonic powers will reply, “Jesus we know, and Paul we know, but who are you?” (Acts 19:15). That person will then find himself running down the street with most of his clothes missing. He would then be arrested for indecent exposure, and in some historic times and places, he would be summarily flogged.

Strain Out That Gnat

Whenever anybody raises the question of our nation seeking to conform our laws to reflect the will of God, it invariably happens that we immediately find ourselves discussing a number of incidents in which professing Christian magistrates behaved badly—flogging Baptists, Salem witch trials, burning Servetus, and the Spanish Inquisition. And this by itself is fair enough. We do need to discuss it, and work through all of that. But discussing it is not the same thing as reacting to it emotionally.

So let’s have a go at discussing it.

When the objector says that these magistrates behaved badly, what do they mean by that word “badly?” As I am fond of asking, by what standard? What standard are we using in order to come up with an evaluation like “badly?” By what standard do we condemn such things? If it is the standard of God, then we have become some species of theonomist. If it is the standard of man, then what is to prevent any honest Christian from giving it the raspberry?

Suppose we bring any kind of moral evaluation into the public square—where that Baptist minister is in the process of being flogged—and we say, “Sir, you must cease!” Suppose the man with the whip turns around and faces us, and says, “Why? Who says?” What do you say? If you say that you come in the name of the Lord of hosts, then we are all advocates of mere Christendom together, and we must then discuss the details of application. But if you say that you come in the name of early 21st century sensibilities, curated by the folks at MSNBC, the man with the whip is going to look over at the magistrates, and they will nod. “Him next.”

The proud secularist stands up straight, and replies that he rejects all such behavior in the name of humanity, and that all such misbehavior should be categorized therefore as “crimes against humanity.” But a crime against humanity just tells us who the victim is, and does not tell us where the standard comes from.

Does the standard arise from humanity? How can moral standards arise from the end product of so many millions of years of blind evolutionary groping? And if that is the source of our standards, then whatever humanity wants to do must be right. And a cursory review of human history would seem to indicate that what humanity wants to do from time to time is burn witches.

If there is no transcendent authority over humanity, then humanity is god. And if humanity is god, then everybody needs to quit it with their backchat. The god is apparently a capricious one, easily annoyed, and so we should learn to just roll with it. Sometimes it wants to pull out the beating heart of victims on the top of Aztec pyramids, and other times it wants to castrate little boys in San Francisco hospitals. Who are you to talk back to your god?

Thus may we dispatch the ardent secularist rather quickly.

How Christians Try to Turn Secularism Into a Reasonable Option

More troublesome is the Christian who has been influenced by all the secularist propaganda. He has a Christian standard of right and wrong operating in the back of his mind all the time, which enables him to jump guiltily whenever the secularists bring up the Salem witch trials, but which he cannot allow to operate in the front of his mind . . . because that would get him labeled an advocate of mere Christendom. If he brought his standards of right and wrong out to the front rooms of his mind, you might be able to see them from the public square, if the curtains were pulled back, and that would be raging theofascism. And so he is left in the unhappy position of dangling between two worlds. Just enough Christian ethical sense for the secularists to be able to charge him and his ilk with misbehavior, but not enough ethical sense to be able stand up straight before lawless thrones. This is why we are such a craven mess.

The only thing He is allowed to assert with any force or strength is that Christ does not want us to structure any of our laws in the light of His character and will. But how could such a thing be consistent with the Lord’s character and will? How would it be possible for the God of the Bible to look down from Heaven on the nations of men and then say, “I don’t care what you people do down there”?

Is it really the case that Christ, the ruler of all Heaven and earth, has left us with only one directive? Is it true that this solitary directive insists that we must make certain to pass no laws in His name, and that we are to take special care not to express any disapproval whatever of Baptist-flogging? If that were the one directive that He has given us, I have questions. The first goes back to my earlier question. If that really is His directive, and we are making sure to obey it, doesn’t that make us theonomic? It is an odd sort of theonomy, to be sure, one that has the one true God insisting that we govern our civic affairs as functional atheists—but who are we to question God?

But this sets up my second question. I am really interested in the exegetical case that advocates for this position might make. Where do Scriptures teach the nations of men to ignore God’s existence, character, nature, and laws? This is an important doctrine, if true, and it would nice to see someone undertake the task of proving it.

One of the ways that professing Christians get away with this incoherence is by wind-surfing on the moralistic zeitgeist gusts. Non-believers tend to go on these periodic moralistic jags and crusades—like the save-the-planet climate change cult, or eradicating Super Bowl domestic abuse, or eliminating sex-trafficking—and so it is that Christians are allowed to jump on these evanescent bandwagons, with their Bible verses and everything. But then it all goes away.

So if we were being consistent, all of this puts us in the position of saying that Christ has no real opinions on any kind of political behavior. Why does that seem counter-intuitive? The answer to why it seems counter-intuitive is that it is so clearly wrong.

We Actually Already Solved This Problem

When we talk about a mere Christendom, we are not talking about something that has never been done before. This is not some utopian pipe dream. This is something we successfully hammered out, and it actually functioned well for several centuries. This is not some chimerical vapor wafting out over the nation from north Idaho, land of religious extremism.

Francis Schaeffer used to remind us that our laws needed to be grounded in a broad Christian consensus. With that as the foundation, it was possible to have an informal Christian settlement, which is what the American settlement was. The word informal did not apply to the Christian part, but rather to the “establishment of a denomination” part. The terms of the American settlement are expressed well in the American version of the Westminster Confession.

“Yet, as nursing fathers, it is the duty of civil magistrates to protect the church of our common Lord, without giving the preference to any denomination of Christians above the rest, in such a manner that all ecclesiastical persons whatever shall enjoy the full, free, and unquestioned liberty of discharging every part of their sacred functions, without violence or danger.“

Westminster Confession, American (23.3)

Every PCA and OPC minister who subscribes to the Westminster Confession—and who has not had a exception to the Confession granted to him by his presbytery at this point—is an advocate of mere Christendom. And what I say to any one of them I say to all of them . . . you are most welcome. Tim Keller, you are especially welcome.

The First Amendment to the Constitution forbade the establishment of a Church of the United States. We have a federal system, with central government and state governments in balance, and at the time the Constitution was adopted over half of the states had formal ties to particular Christian denominations—e.g. the Congregational Church in Connecticut. If we have a national bird, the bald eagle, and the different states have their respective birds, this does not set the stage for any kind of civil strife. The same is not true of a national denomination and a state denomination. So the Founders wisely decided not to do that. Establishment at the state level may not be a good idea—I believe it is not—but it is manifestly not unconstitutional.

But the separation of church and state is not the same thing as the separation of God and state, or morality and state, or right and wrong and state. Who in their right mind wants the state to function without any reference to justice?

And this is where certain logical realities decide to deliver to us a well-deserved kick in the teeth. Justice is manifestly, obviously, and clearly a concept that must be theologically grounded. If there is no theological ground for justice—meaning a grounding in the nature and character of Almighty God—then there is no such thing as justice. So if you are not willing for a mere Christendom, then when it comes to standing up for the oppressed (whatever that is), you really ought to save your breath for cooling your porridge.

If a Christian, denuded of all theological justifications, tells the bloodthirsty state to stop killing the babies, and they turn and ask, “Why should we?” he has nothing to say. And because he has nothing to say, he might as well go home and check out his Netflix queue. As many have.

Why Baptists Need a Warm Invitation

In Stephen Wolfe’s book, he acknowledges that Baptists have a key role to play in all of this. At the same time, he says that because he is not a Baptist he is not equipped to do the theological work necessary to fit the proposal within a Baptist framework. That, he says, is a task to be taken up by the Baptists.

I would go a step further. I would say that at this point in American history, pulling our country back from the brink of the Abyss is not going to happen without the Baptists. We need the Baptists to take up the challenge that Wolfe presented. We need the Baptists to do the work necessary. As far as we Presbyterians are concerned, there is plenty of room in mere Christendom for the Baptists. But for you all to do that work, you will need to focus a lot less on the Obadiah Holmes incident, and a lot more on how many millions of babies have been slaughtered under the current settlement. You need to think about how many hundreds of abortion clinics there are, and then compare that to how many thousands of churches there are. And then ask yourself how that could have happened.

A Baptist framework for action is either possible or it is not possible. If it possible, then do it. Baptist leaders need to be raised up to lead their people in a mere Christendom direction. Lay out the map, and urge the Baptist foot soldiers to follow that map. If it is possible, then somebody needs to do it. Now would be a good time.

But suppose you say, shaking your head, that it is not possible. “There is no consistent theological framework that would allow Baptists to declare the Word of God about anything to the civil magistrate.” Allow me to speak bluntly. If you really believe that, then your only ethical option is to leave off being a Baptist. Saving children from slaughter, mutilation, and slavery should be more important to you than “not baptizing them.”