Introduction

A few years ago, Logos School adopted a logo for her athletic teams that some folks found strange or odd, and some found distinctly unbiblical. In actual fact, it was not all that strange or odd, depending on one’s knowledge of the broader historical context. So with that said, here is a brief historical sketch that sets the stage for the statement that Logos made about it, with which I will conclude.

Here is the Logos crest off to the right—a crowned skull, so you can keep it in mind as we go. And then there is a close-up of the skull.

Pirates or Poison

What are the central modern connotations? What most modern folks would think about if asked what a skull symbol meant (either with just a skull, or even more, with a skull and crossbones) would either be pirates or poison.

So there’s your standard pirate, which is perhaps what most moderns think of. The skull and crossbones is on his hat there, and when that same symbol is on a black flag, it is universally recognized as the Jolly Roger. When you see that flag flying. you know that a boatload of antinomians is sailing toward you, and you can expect a rough time of it. It is not a boatload of godliness.

Poison is the other thing that this symbol means in the modern world. If you wanted to make sure that nobody drank from a tainted water fountain, and the fountain in question was in an international airport, with every language known to man coming through there, how would you warn them off?

The answer to that question is off to the right there.

More Historical Uses

But what about previous centuries?

On the one hand, we can see that people in other eras did not have the same reaction to this symbol (and to human bones) that we do. They appeared to take the presence of death much more in stride. Sometimes we can chalk this up to different customs and mores, and it really is just a cultural variation, like differences in clothing or foods.

For example, in the time of Christ, the burial custom among the Jews was to place the body in a cave, and allow it to decompose. You would come back after a year, gather up the bones, and place them in a small box (called an ossuary), and place the ossuary on a shelf in the back, alongside all the other deceased relatives. In other words, there was a lot more direct contact with the bones of your ancestors, and it is not surprising that they had a different attitude toward those bones. Some archeologists believe that we have actually found the ossuary of James, the Lord’s brother. By way of contrast, our modern American burial custom of “six feet under” puts a lot more distance between us and the deceased (except in New Orleans, which is a lot closer to the custom of the Jews).

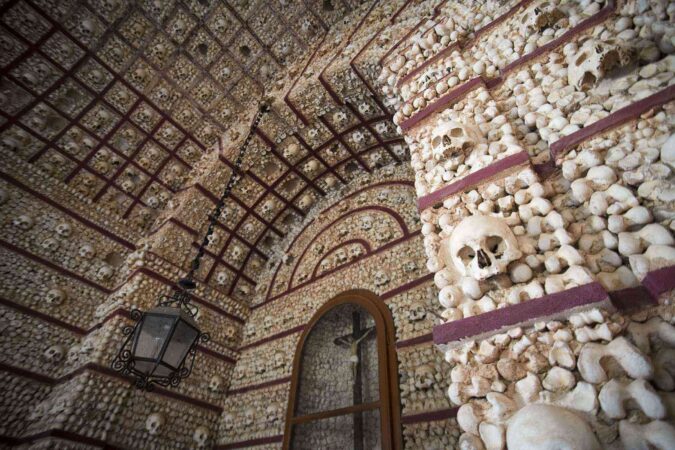

But at other times, we would probably say that they were being just plain weird and macabre. There are times when we must say, “Something was wrong with those people.” For a case in point, or at least what I would consider a case in point, here is a strikingly beautiful church made entirely out of human bones. And there is more than one of these scattered around Europe.

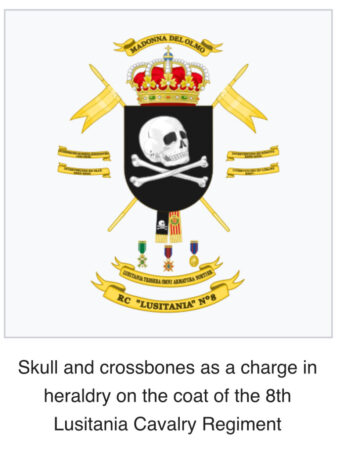

Then there are times when the imagery was simply intended to communicate a tough-guy vibe, as you might expect with a military unit. Here is some heraldry from a European cavalry unit. A quick glance at it reveals that something very different from a Hell’s Angels leather jacket is going on. You can see here an odd juxtaposition (to us) of the skull and crossbones with ribbons, flags, medals, a crown, and so forth. The image is one of aristocratic death dealers as opposed to the Harley-riding antinomian death dealers. The toughness would be common to both, but there would be striking differences as well.

This was the connotation that we were trying to evoke with one of my book covers. It was the connotation of what some might consider “outlaw” behavior, but not really, and on the other hand, the toughness of the military use, combined with a black Geneva gown. A study in contrasts, so to speak.

Memento Mori

“So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom.”Ps. 90:12 (KJV)

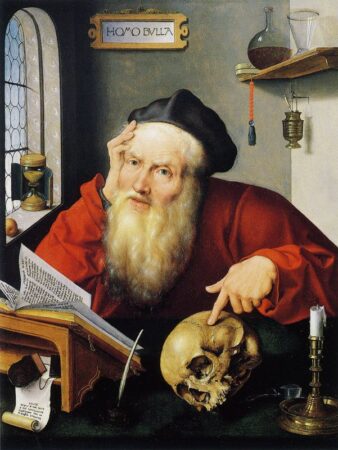

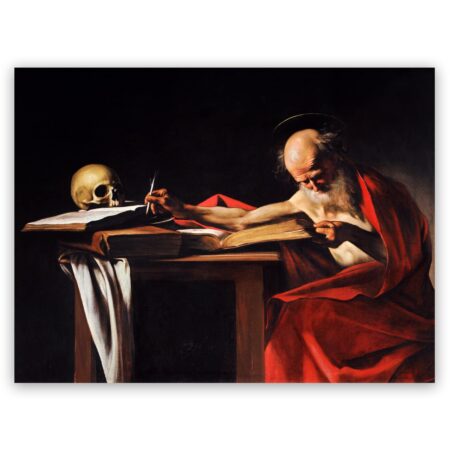

There is also a long history of a meditative and devotional use of the skull. Medieval scholars used to keep a skull on their desks in order to remind them that they too were mortal, and that they should always keep the day of their dying in view. Here are a couple of images of Jerome at his studies.

This “memento mori” theme may have had its origin with a custom that the pagan Romans had. If it did, it provides us with a good example of common grace. According to some accounts, when a commander came back from the wars in triumph, he was given a triumphal procession. In the chariot with him was a slave, called an auriga, who did two things. He held a laurel crown over the victorious commander’s head, and he would also periodically whisper to him, “memento mori.” Remember that you are mortal. Not all of them did.

But whatever the origin, this was still a straight forward application of Scripture—teach us to number our days.

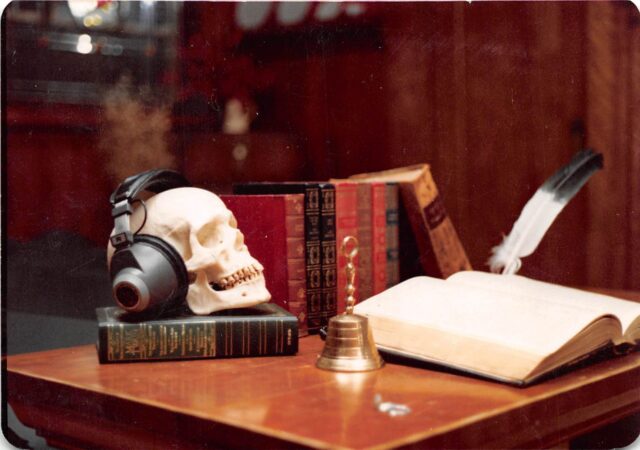

A number of years ago, when I was more involved in making music than I am now, I recorded an album that was called Falling on Deaf Ears. The imagery on the cover was taken from this medieval practice, but with a twist. Jerome did what he did so that he would remember that the day was coming when his skull would be just like that one on his desk. That has actually now happened, we may note, in that Jerome has long since been dead.

But the image on the album cover was meant to portray the skull itself not paying attention to what was going on. A skull with headphones makes no sense—there are no ears, just holes.

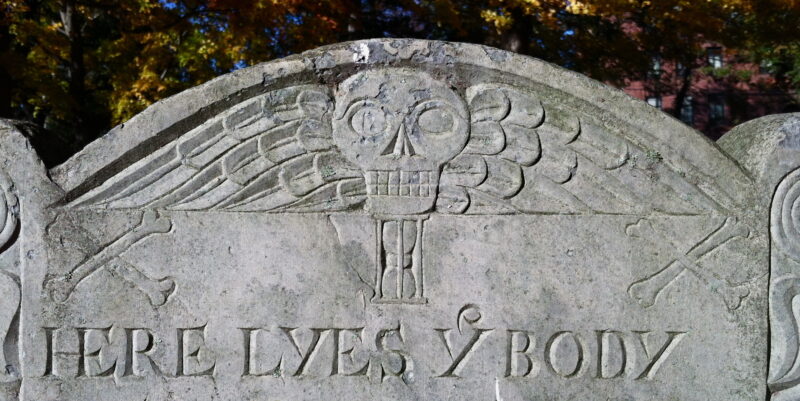

Puritan Gravestones

Apparently carrying over a medieval tradition, it was also common for the Puritans to decorate their tombstones with a skull and crossbones. It is in all likelihood where the pirates got the idea for their symbol. Here are some samples of that kind of thing.

On the second one, it does not have the crossed bones beneath the skull, but has a pair of them, one on the right and the other on the left. Obviously, the Puritans were not attempting to make us think of pirates or poison. The connotations of what they were doing would not easily map onto what would be happening if a modern Christian requested this for his tombstone.

In an old churchyard in Annapolis, Maryland (St. Anne’s, at Church Circle), I once saw a gravestone very much in this tradition.

A Biblical Note

Up at the beginning, I noted that some Christians might feel that there is something fundamentally unbiblical about using skull imagery—however historical the practice might be. But this is a place where Scripture surprises us.

Three of the four gospels go out of their way to explain the etymology of the place where Jesus died. It is a verbal image, true enough, but it remains an image for all that.

“And when they were come unto a place called Golgotha, that is to say, a place of a skull.”Matthew 27:33 (KJV)

Mark says much the same.

“And they bring him unto the place Golgotha, which is, being interpreted, The place of a skull.”Mark 15:22 (KJV)

And John puts it this way:

“And he bearing his cross went forth into a place called the place of a skull, which is called in the Hebrew Golgotha.”John 19:17 (KJV)

Many Christians assume that the hill where Christ was crucified was a hill, shaped something like a skull, and the executions occurred on top of it. If that is correct, then it is striking that the cross of Christ was driven into the earth, delivering a mortal head wound to Death itself.

But there is another tradition that holds that the place of the skull was a cliff face that was right next to a major thoroughfare. That location is at least plausible, as can be seen above. This would fit with the Roman practice of wanting their executions to be as public as possible, and it would also explain why Pilate wanted that sign above the Lord’s head, where all could easily read it.

In any case, just as the cross—an instrument of gruesome torture—became a universally recognized symbol of the Christian faith, so also the gospel writers wanted the skull to receive its due—which actually happen. The Aramaic word for skull was golgotha, and three of the four gospel writers made sure we understood that. The Latin word for skull is calvarium, from which, of course, we get Calvary. How many gospel hymns have picked this symbol up? The gospel writers emphasis did not go unnoticed.

Connotations

All forms of communication utilize both denotation (what something means) and connotations (what it makes you think of, or feel like). If a person’s experience with this symbol is negative, then it is understandable that he might have a hard time with people using it devotionally, or even humorously. Say that a loved one, for example, is in rebellion against the Christian God, and he expresses this by getting a tattoo of a skull with the serpent from the Garden crawling out of its eye socket. Such a person might have a hard time seeing the Logos logo in a positive light. That reluctance should be honored and respected, as the apostle instructs us.

At the same time, that experience should not be made authoritative. We have thousands of years of other people seeing things differently. This should therefore be an area where we diligently apply the apostle Paul’s teaching about adiaphora.

“Who art thou that judgest another man’s servant? to his own master he standeth or falleth. Yea, he shall be holden up: for God is able to make him stand.”Rom. 14:4 (KJV)

And with all of this said, here is the . . .

Logos Statement

“The skull is part of our crest and represents one of our three declarations: Sacrifice. The skull is crowned for two reasons: First, because all earthly glory goes into the grave, all earthly glory must be sacrificed. But, more importantly, this image is a reference to the ultimate sacrifice: the King who laid down his life for the world on Golgotha—the place of the skull. This motto and crest calls us all to imitate Him. We are trying to train Kings and Queens who will see His act of sacrifice as the true glory of leadership. In addition, the use of the skull undercuts the potential soft fanciness of using a crest at all and leans into masculinity.”