Introduction

As I have been observing the debate over Christian nationalism deve . . . well, develop is not really the right verb. Stagger is more like it. As I have watched the debate over Christian nationalism stagger around, perhaps toward resolution, a few thoughts have occurred to me from time to time. Actually, one basic thought has occurred to me over and over and over again, and so naturally I thought I should tell you about it.

When men from disparate backgrounds and perspectives all seem to be sharing the same fundamental misunderstanding, some of them innocently and others not so much, it makes me want speak to that misunderstanding. I have seen it in Michael O’Fallon, James Lindsey, Tim Bayly, Michael Horton, Scott Clark, and D.G. Hart. There is one common misconception running underneath all of their criticisms of “a Christian prince,” and so I thought to address it here.

I am going to attempt to put this response of mine in a nutshell, but what is more likely to happen is that I shall wind up putting the same response into a handful of different nutshells. But it doesn’t really matter which nut you pick first. It is all the same basic point anyhow, and that is why they all taste like sweet walnut. And I might as well give you the bottom line now.

By what standard?

The Voice of the Lord

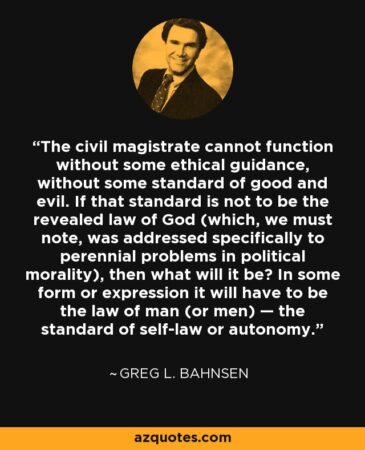

All ethical judgments, in order to be ethical judgments, require a transcendental grounding. Otherwise, they are not ethical judgments at all, but rather just the opinions of some guy, or maybe some other guy. In James Lindsey’s case, they are just the burbling of certain protoplasmic chemicals, reacting as they always would under these conditions and at this temperature. Whatever the case, they have no authority over me at all. Neither do they have any authority over us, us being the body politic.

Again, in order to be an ethical assessment at all, it requires transcendental authority. In short, there is no ethical authority whatever without a “thus saith the Lord.” Our secularist experiment functioned for a time as though we could do without His Word, but this was merely a sensation—akin to the sensation of flying that was felt by some inventor kid with Batman wings who jumped out of the hayloft.

So ethical judgments require an ultimate standard. But this necessarily includes all ethical assessments of the dire threat posed by Christian nationalism. In short, you can run, but you can’t hide.

Christian nationalism is the view that we cannot order our corporate lives together without reference to the divine. We cannot govern ourselves appropriately without reference to God. We need Him. That is the view. That is what we are saying.

The retort to this view—the misunderstanding mentioned at the top—is frequently wrapped up with various examples drawn from the long and sinful history of the first Christendom—the Spanish Inquisition, the Salem witch trials, the Thirty Years War, the 12th century pogroms in London and York, all overseen, in some way or other, by various Christian princes. So given their record, why are we so hot for Christian princes? Hey?

It seems like a tough question, but the problem is that there is no real way to bring these historical charges against Christian nationalists without assuming the legitimacy of Christian nationalism.

Did Christ disapprove of these outrages? And if He did, then isn’t our complaint against these Christian princes the fact that they were being disobedient? That they weren’t being Christian enough? That their Christian nationalism didn’t go far enough?

But if you go the other way, and say that Christ has no negative opinion of these outrages, then the natural question of “why should we care then?” arises. Few would take that route, right? But this means that few would abandon the ideal of Christian nationalism.

Say that some Christian prince decides to harass the Jews. As we all would grant, he is not acting like a Christian. But—and this is where I turn to our interlocutors—is he supposed to act like a Christian or not? If he isn’t, then what’s your beef? You say he is not supposed to act like a Christian, and he isn’t. But if he is supposed to act like a Christian, then how is that not Christian nationalism—you know, “appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of his intentions”? Incidentally, I cribbed those words from the ravings of some other extremists of yore. Depending on where you were educated, you may have heard of them.

And this is what gets me. James Lindsey is an atheist who is distressed by living Christian nationalists because they are supposedly abandoning the ethos of the Founders, consequently posing a threat to his liberties, when the fact is that back then he would have had a lot less freedom of cultural engagement than he does now. He opposes contemporary Christian nationalists because they threaten to take him back to the era of his heroes. He thinks he is lionizing James Madison when he is actually lionizing Earl Warren.

Bringing the Absolute Down Within Reach

Okay, we filled up one or two nutshells. Let’s come at this another way. Is Christian nationalism bad? A lot of people are acting like it is bad. But who says? By what standard? What is the basis for making moral judgments about any political system whatever? If the standard of judgment originates from some location below the transcendental ceiling, then the only authority it possesses is that of power. That is why our secularist overlords are acting the way they do. “Shut up,” they explain. To channel the late Francis Schaeffer, if there is no absolute over society, then society becomes the absolute.

But speaking frankly, between us girls, as I look around at this dog’s breakfast of a culture, I am disinclined to make it my absolute. I don’t want an absolute that floats on a sea of red ink, that mutilates little boys and girls, that marries dudes to one another, and that walks around like it is the civilizational equivalent of the smartest guy in the room, while at the same time being the one that is always bumping into walls and knocking over vases.

Instead of Talking Nonsense

Now our critics could evade the force of this reasoning by leaning in and owning it. They could say something like: “Yes, well, Christian nationalism is actually a noble ideal and your points about its being an inescapable reality are well taken. But our problem is actually with you Christian nationalists. Your noble cause deserves better champions. We don’t trust you. You speak as though the secular order is coming apart at the seams, and you are positioning yourselves to assume responsibility and rule once that disintegration is complete. That’s as may be, but we think that you guys are singularly ill-equipped to do anything like that. We think that you could not run a taco stand, much less assume responsibility for the restoration of Western civilization.” Or other hurtful words to that effect.

As much as we regret how this would have descended to personalities, it at least has the advantage of not being incoherent. And one would see their point, of course, if only they would make it. If you would give me a minute, I’ll bet I could round up some Christian nationalists who specialize in idiot memes, and who think that what America needs right now is the dynamism of a Bonaparte, only a Christian one. But it will not do to read one or two such memes from the fringe, and then pretend that that is what Stephen Wolfe was advocating in a book they didn’t read. A common retort from our side, and one that lands on the jaw is this: “Do the reading.”

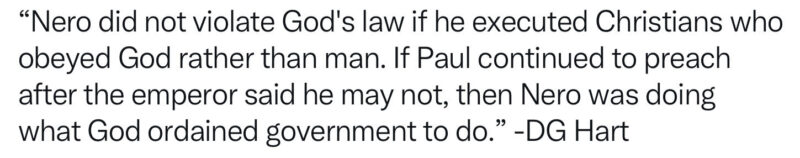

But instead of making that point, which would at least be intelligible, we get things like this from D.G. Hart.

When I look at that, I am not quite sure where to look. It makes me want to not make eye contact with anybody. This Christian gentleman is telling us the story of Daniel’s three friends getting pitched into the furnace, and is seriously maintaining that we have to keep in mind that Nebuchadnezzar was perfectly within his ordained rights to throw them in there. This is a new take on Bible stories indeed.

John Stott once said that fuzzy thinking was one of the sins of the age. We have to do better. To the critics of Christian nationalism, I would urge three things upon you. First, do the reading. Fight with what we are actually arguing for, and not with what might be an easier position to refute. Second, don’t charge us with advocating for things that we abhor as much as you do. And third, if you object to our (only apparent) surrender to the Balkanization of America, you can’t fight that by accelerating the Balkanization of the conservative Christian resistance.