Introduction

Within the last few weeks, Scott Clark circulated a quote from Southern Slavery as It Was, and then Anthony Bradley retweeted it. As a consequence, that whole business got chased around the block a few more times. I really don’t think that anything I might say here will persuade those particular gentlemen of my sincerity and good will, but in thinking about the quote they cited, and the fact that many friends of our ministry continue to get asked pointed questions about it, I thought I should say a little bit more about it here.

Background

To review, Steve Wilkins and I co-wrote Southern Slavery as It Was back in the nineties. In case you are interested, here is a bit of history behind that booklet—link. After (real but inadvertent) citation problems were discovered in the booklet, we pulled it from circulation immediately and did so because of those citation problems. But because of the controversy that was going on, and because of questions about what my views actually were, I subsequently published Black & Tan which contains the basic outline of my views on the subject of slavery and the South. That book contained reworked material from my contributions to SSAIW, as well as a good bit of additional material. So if people want to know my views on the subject, my practice has been to refer them to that second book.

But I have also found that a number of my adversaries like to ignore the very existence of B&T, which is not surprising, in that it was heartily commended by Eugene Genovese, one of America’s premier historians of that period in history. And so they merrily continue to quote from SSAIW. This creates problems for some of our friends, and so they wonder what I would make of those specific statements now.

Quite apart from the citation problems, would I want to recast or disavow or explain or contextualize or modify certain views expressed as excerpted from SSAIW? The short answer is yes, I would. If I were to try to express such a sentiment today, how would I go about it? I would want to make some corrections, qualifications and adjustments, and that is why this is tagged under Retractions.

At the same time, I am not under any illusions here. The people who were mad at me before will continue to be mad. I do believe that the point can be made more carefully and accurately, but I don’t believe the historical truth is any closer to being politically correct or woke than ever it was. So wish me luck. And also, by the way, I ran a draft of this response by Steve Wilkins, and we continue to be in agreement on this subject.

The Quote

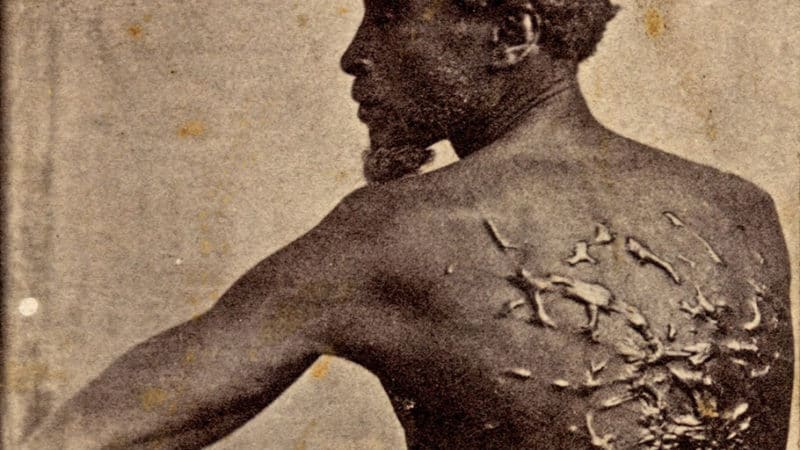

So here is the quote that was being circulated, along with an ominous looking photo of your truly:

“Slavery as it existed in the South was not an adversarial relationship with pervasive racial animosity. Because of its predominantly patriarchal character, it was a relationship based upon mutual affection and confidence. There has never been a multi-racial society which has existed with such mutual intimacy and harmony in the history of the world. The credit for this must go to the predominance of Christianity. The gospel enabled men who were distinct in nearly every way, to live and work together, to be friends and often intimates. This happened to such an extent that moderns indoctrinated on ‘civil rights’ propaganda would be thunderstruck to know the half of it. Slave life was to [the slaves] a life of plenty, of simple pleasures, of food, clothes and good medical care. In spite of the evils contained in the system, we cannot overlook the benefits of slavery for both blacks and whites . . . Slavery produced in the South a genuine affection between the races that we believe we can say has never existed in any nation before the War or since.”

Southern Slavery As It Was

The basic problem with this is that, as the adage goes, it is possible to drown in a river that is, on average, only six inches deep. There were horrific abuses in the Southern system, which the booklet acknowledged, and there were other places that were very much like what is described above, as the booklet maintained. But the quote above intimates (although it does not say) that the abuses in the system had to have been rare enough that they could not be taken as characteristic of the system as a whole. At the same time, the War was a severe judgment on the system as a whole—the judgment of the War was God generalizing, and there was righteousness in that generalization. This was acknowledged in the booklet also, but I don’t think it was emphasized or underscored the way it should have been.

If I were to tackle this topic today (which I guess I am doing right now), I would not want to use any words that implied that I knew how to quantify the two kinds of experiences precisely. I would not want to say anything like most, or almost all, or anything like that. I would content myself with saying that there were “many” horrific abuses, and that there were “many” situations that were characterized by benevolent masters, and leave it at that.

A modern point of comparison would be America’s complicity in the abortion carnage. On account of the millions of lives lost, we are most worthy of the judgment of God. God could rain down fire on all of us, and it would be richly deserved. It would be appropriate for subsequent historians to examine how many Americans opposed abortion, and who loved and cared for their own children. But it would not be appropriate for them to do so in a way as to make it seem that the judgment itself was unjust.

The Way of the Ideologue

I said above that there were “many” atrocities, and also that there were “many” benevolent masters. Why do I say that?

I will answer the question, but before I say why, let me say something about the misrepresentations of many of our critics on this point. To say that there were more benevolent masters in the South than is usually thought is not the same thing as saying that the wicked and cruel masters were actually benevolent. One thing the booklet was clear about was that appalling behavior should be treated by everyone as appalling behavior. And so those who believe that Steve and I were defending cruelty as though it were kindness are people who are selling something.

So if someone wants to say that there was nothing but atrocities all the time, that is a position that is taken for the sake of hard ideology, and is historically indefensible. And if someone wants to say that it was all Uncle Remus all the time, maintained for the sake of a Lost Cause romanticism, that is also indefensible. And taken in isolation, the quote above from SSAIW seems like it wants to go in that Uncle Remus direction.

So here is why I say that there were quite a number of cruel masters and benevolent masters both. During the Depression, FDR’s New Deal put a bunch of people to work interviewing former slaves, and collecting their testimonies. I am currently reading those Slave Narratives, and there are many examples of both kinds of masters in there. And so this is why I feel comfortable saying “many” in both directions, and a few somewhere in between.

Here are some samples, and they are all over the map.

“One of my aunts was a mean, fighting woman. She was to be sold and when the bidding started she grabbed a hatchet, laid her hand on a log and chopped it off. Then she throwed the bleeding hand right in her master’s face. Not long ago I hear she is still living in the country around Nowata, Oklahoma.”

Slave Narrative (Loc. 253)

“She was a fine woman. The Brown boys and their wives was just as good. Wouldn’t let nobody mistreat the slaves. Whippings was few and nobody get the whip ‘less he need it bad. They teach the young ones how to read and write; say it was good for the Negroes to know about such things.”

Slave Narratives (Loc. 393)

“The white folks on the next plantation would lick their slaves for trying to do like we did. No praying there, and no singing.”

Slave Narratives (Loc. 398).

“Dey used a plain strap, another one with holes in it, and one dey call de cat wid nine tails which was a number of straps plated and de ends unplated. Dey would whip de slaves wid a wide strap wid holes in it and de holes would make blisters. Den dey would take de cat wid nine tails and burst de blisters and den rub de sores wid turpentine and red pepper.”

Slave Narratives (Loc. 421).

“The only pusson I ever seen whipped at dat whipping post was a white man” (Loc. 455).

Slave Narratives (Loc. 455).

“Dey sure never did whip one of Master Holmes’ n*s for he didn’t allow it. He didn’t whip ’em hisself and he sure didn’t allow anybody else to either.”

Slave Narratives (Loc. 527).

“Old Master was good to all of his slaves but his overseers had orders to make ’em work. He fed ’em good and took good keer of ’em.”

Slave Narratives (Loc. 691).

“Old Master was a fine Christian but he like his juleps anyways. He let us n*s have preachings and prayers, and would give us a parole to go 10 or 15 miles to a camp meeting and stay two or three days with nobody but Uncle John to stand for us” (Loc. 924).

Slave Narratives (Loc. 924).

So the idea of the benevolent master is not a myth, The idea of the horrific taskmaster is no abolitionist myth either. In the citations above, you can see obvious examples of each, and such contrasting narratives are not hard to come by.

I said above that I did not want to quantify in either direction, other than to say there were “many” examples of both. But I will say this much. On the one hand, the entire population of the South was 9 million people, which included 4 million slaves. The South fielded about 1 million men for the war, which meant that most of the able-bodied white men were away from home. In contrast, the North had about 22 million people, and a million men in the field. This meant that many of the farms and the plantations continued to operate with slave labor and absent masters during the war, which is hard to imagine if they had all been nothing but hellholes.

On the other hand, as argued above, we should not assume that the judgments of God are based on our calculations of acceptable and imagined ratios between benevolent and cruel masters. We don’t get to take a vote on when God will be allowed to place us in His holy balances. So there had to be enough wickedness in the laws and in the actual treatment of slaves to warrant the kind of fearsome judgment that came.

In Sum

So while there were many instances within American slave-holding in which many blacks and whites did have genuine and godly affection for one another, we cannot say it was characteristic of the institution as a whole. We are not in a position to say this because of the judgment that fell. The problems became more pronounced as things moved toward the Civil War—e.g. slavery in Jonathan Edwards’ day in New England was not the same sort of thing as slavery in Alabama in 1850. And as the war approached, the laws in the South grew increasingly draconian. So we can surmise that American slavery was a wicked institution on the whole because God brought a cataclysmic judgment against the entire nation because of it.

One last point. Keeping all these principles in mind, we have to remember that we are a wicked generation ourselves, and richly deserving of judgment ourselves. We are far more guilty than they were, and despite our corruptions, far more insolent in our conviction that we are paragons of virtue. What we actually are would be closer to paragons of virtue signaling. Consider Roe, and consider Obergefell, and we are simply asking for it.

In other words, to reflect on the historic judgments God has brought upon our people is not an academic exercise. It is one we ought to pursue in the interests of learning spiritual wisdom.

“Therefore thus saith the Lord God of Israel, Behold, I am bringing such evil upon Jerusalem and Judah, that whosoever heareth of it, both his ears shall tingle.”

2 Kings 21:12 (KJV)