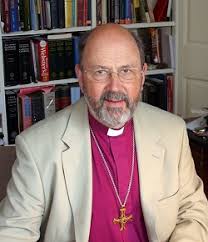

Some friends have drawn my attention to a piece that N.T. Wright wrote for Time on the coronavirus here. Another friend of mine has already replied to him here, and just like my friend I agree that the article was better than the headline, which was gobsmackingly bad. But the article itself was still a swing and a miss.

So there are lots of things going on in my world right now, so let me limit myself to just two rejoinders.

The first thing to say is that it is not a coherent response to argue that we cannot know what God is up to with the coronavirus, and then turn around and assume in the nature of our response that we have some idea of what it means. Either we know or we don’t know. And if we don’t know, then we don’t know if lament is the appropriate response. There is an assumed meaning in lament, and you can’t have that meaning if you don’t have any meaning. Jews who had a promise of a return from exile, and a sense of their own vocation as a people, could lament their absence from Jerusalem. But the merchants of Babylon could not lament in this sense — all they can do is wail over their losses (Rev. 18:19).

The Scriptures teach us that disaster comes from the hand of God. “Shall a trumpet be blown in the city, and the people not be afraid? Shall there be evil in a city, and the Lord hath not done it?” (Amos 3:6). Wright is fully correct to say that God Himself laments; He does. But the great mystery for us concerns how God laments those things which He Himself decreed would come to pass. So we do not say that God laments. We must say that the sovereign God laments.

And so the fact that God has done something by itself does not automatically tell us what God has intended by it. Our interpretation of that should be dictated by other factors, and there are a range of possibilities. The one place in the New Testament where God’s people say hallelujah is when the smoke of Babylon rises forever and ever (Rev. 19:3). If we don’t know the meaning, why could that not be one of the possible meanings?

But I agree that we should be careful when speaking about such things. We must not jump to conclusions. We must proceed cautiously. This is because we have a tendency to think that our own lights are the same thing as the light of the Word. But abandoning that peculiar form of pride should not lead us into another form of pride, which is that of thinking that God’s Word does not shine any light into the darkness of this world at all, which is what Wright’s headline said, and which his article implied. God’s Word says a multitude of things that apply directly to us now in our current situation.

So this leads to the second thing. The Bible tells us that God’s dealings with mankind are often mysterious, and so we should never rush to glib explanations. But His works are not absolutely inscrutable. When Jesus rebuked the people for misreading the collapse of the tower of Siloam, and for the incident where Pilate killed the men of Galilee (Luke 13:1-5), He rebuked them, not for reading meaning into the story, but for having read the wrong meaning into the story. The hot take on the streets of Jerusalem was that the men who had died were extraordinary sinners, and that their deaths were God’s judgment on them. Jesus said the true meaning, which the people should have apprehended, was these deaths were a harbinger of the coming judgment on the whole city of Jerusalem. It was a warning shot across the bow. But people insisted on thinking that the dead should have repented, while Jesus said that the meaning was that the living should repent.

And this leads us to what I take as the central meaning of this difficult disease, and our fearful and panicked and guilty and most destructive reaction to it. As a nation we deserve God’s judgments, and we deserve far worse than what we have gotten thus far. We are praying that God might stay His hand. But why should He? If He does stay His hand, is June still going to be pride month? If He does stay His hand, will the slaughter of American babies by the metric ton pick right up again? If He does stay His hand, will we continue to vaunt our secular little selves, pretending in our insolence that we have no king but Caesar?

N.T. Wright wrote his article as though we should simply lament our losses, instead of lamenting our sins. His one mention of sin was when he said that to think about something like that would be self-centered. He urged upon us the lamentation of loss, and not the lamentation of a richly deserved loss. So this misses the example of Ezra, a man who led people back to their heritage through repentance. A simple lamentation of loss is what Wright summoned us to, but this is a response that a merchant of Babylon is fully capable of offering up.

But in one way it is fitting. Why shouldn’t we wail like the merchants of Babylon did? That is almost exactly what we are. We have ten times the riches that they had, and (apart from repentance) exactly the same amount of hope.