Please note well: If you order this book in hard copy, it will ship before Thanksgiving. Link here.

Larry Locke

Larry Locke did not look at all like a successful author. In his late twenties now, he had made most of his living as a logger in Montana. He had started at that when he was sixteen, and worked around his school schedule, and had done the same through college. He had managed to work full time, and graduate on time. And his looks belied him. He was 6 foot 10, and about 300 pounds of hardened muscle. That wasn’t the part that belied him because he looked like a logger from Montana. He was also a wolf and bear hunter, and he looked like those two things also.

It was the successful author part that threw people. Four years before, he had walked into the DC offices of Aegis Imprint, and plopped a manuscript down on the desk of the receptionist. He had asked her, very politely, how these things were usually handled, and who he should show his manuscript to. The receptionist, normally very adept at handling walk-ins who knew they were supposed to be big time successful authors, was freaked out by Larry’s size, not to mention his apparent outlook on life. She squeaked something like “excuse me,” and darted into the office behind her, that office belonging to Ken Corcharan.

He was the founder, owner, and publisher of Aegis Imprint, a wildly successful publisher of inflammatory conservative books and magazines. He was a hard case, with a straight-line edge, but not a sociopath. That said, if he ever got bitten by a diamondback, the snake would be the one that died. At the same time, he was a shrewd judge of horseflesh, so to speak, which is how he got to the place where he was. When we refer to him as a hard case, we are talking about his demeanor toward competitors, not toward his authors. He was astonishingly generous to his authors.

In fact, he was asked about that once in an interview with Publishers Weekly, and he said that the normal practices of the publishing industry seemed to him to border on the insane. “Publishers cozy up to their social peers among the competition, and schmooze around like there is no tomorrow, and then turn around and treat their authors like they were the competition. But if I were the owner of racehorses, I wouldn’t be chumming around with owners of other horses, who wanted me and my horse dead, but until that glad day arrived would willingly invite me to their parties on Martha’s Vineyard. And then to compensate for such lunacy, would I feed all my horses on cheap oats?”

This parable was a dark saying for most readers of Publishers Weekly, except for the authors. The authors liked it.

But meanwhile, back at Aegis Imprint, the receptionist, whose name was Mindi, was pleading with Ken to come out and handle this one. Please.

And so it was that Ken came out, shook Larry’s hand, and said pleased-to-meetcher, and told Larry that he did have fifteen minutes to spare, and to come right in. Larry picked the manuscript up from the receptionist’s desk and brought it in with him, and plonked it right in front of where Ken usually sat. He didn’t even have to bend over to reach across the desk.

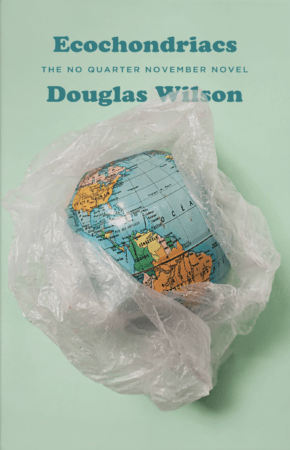

Ken had looked at the title page, which read, simply, Ecochondriacs. He flipped over a few pages until he got to the intro- duction and read the first three paragraphs, at the end of which he fully came to grips with the discordant note that was being struck somewhere in his brain.

The man sitting in front of him was a total unit, like two or three Navy SEALS packed into one. Moreover, he looked like a logger, the kind that could walk out of the woods with a tree under each arm. And yet . . .

“You write this yourself?” Ken asked. Larry had nodded.

“Yes. Yes, I did.”

The prose read like it had been written by the archangel Gabriel—when the muse was on him, when he was writing hot, and was going real good. Ken sat back in his chair, and stared at Larry for a moment. Then he stared for two moments.

“Look,” he said, leaning forward. “This is not how it happens. This never happens. It doesn’t work this way. Don’t tell anybody about it. But you have yourself a book deal.”

But it turned out that those three paragraphs that Ken was gambling on were actually kind of pedestrian compared to later passages in the book. Larry had a huge gift for making com- plicated issues plain, and to do so without distorting what the actual issues were. He wrote intelligently and with verve. He wrote with authority, and not as the scribblers.

And that is how his book had made it into the stratosphere of book sales. It was the most successful book that Aegis had ever published, which was saying something, and it even elbowed its way to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, and was still, a few years later, bouncing along at the top of the Amazon rankings.

As a consequence of all this, Larry had found himself with more money than he knew what to do with. That had lasted for about three months, after which he figured out through some hard thinking what he was going to do with it all. He was a quick study when it came to piles of money, and those close to him were all pleased that it did not go to his head, not even a little bit. He bought a remote lakeside cabin back in western Montana, free and clear, on a 140-acre parcel in the mountains. That was where he was going to live, and fish, and hunt, and write some more great literature. He was going to do his part to save Western Civilization, but he was going to do it with a backdrop of gorgeous mountains. Why not? he thought. Calvin wrote his commentaries with the Alps right there.

But he also bought two pieces of property in the DC area. One was a condominium, a place to hang his hat while trying to talk sense into congressmen, which was a strenuous activity in its own right, and the other was a medium-sized office complex on ten acres. This latter property was the headquarters of Eco- sense, an organization dedicated to the restoration of ecological sanity. And the founder and president of this entity was Lar- ry Locke himself. He defined ecological sanity as a world that didn’t have any environmentalists in it anymore, except three at the South Pole perhaps, studying the weather. Not the climate, but the weather.

The name Ecosense initially gave visitors a warm glow, the kind you get when dealing with reasonable conservatives, the kind who are quietly selling the farm while trying to keep Grandma, sitting there in the front parlor, reassured that nothing like that could ever happen to the family dairy that we all hold so dear. But when you drove up and parked in the front lot of this particular organization called Ecosense, you started to get a different vibe. Or you did as soon as you got out of your car. The first thing that struck you was the fact that there was a large pillar right behind the flagpole on the large, grassy circle that you had to drive around to drop someone off at the front door. On top of this stout pillar, about fifteen feet up, was a stretch Hummer, jet black. If you went and stood by the base of it, you could hear that the Hummer was running. It was running all day and all night, virtually all the time. Part of the maintenance man’s night shift duties was to come out at 4 am and turn it off for a half-hour respite, gas it up, and have it going again by 6 when the first staff workers started arriving.

“We don’t know how long that beast can go,” Larry said. “But we will find out. And then when it konks, we will just have to get a new one.”

“But . . . but why?” A reporter had once asked, querulously. “Because CO2 helps keep the vegetation green. We are a green organization all the way, baby. I mean, look at those bush- es over there. That hot Hummer air is mother’s milk to them,” Larry had replied. And he had said no more about it.

Ecosense was an organization filled to the rafters with eco-resistance radicals. And by eco-resistance, I mean resistance to the environmentalists, and not resistance to those evil corporations that go out and find the fossil fuels that keep us all happy and warm. And by rafters, I mean the laminated kind that were put together in a big factory using a lot of industrial glue. It was a special point of pride for Larry, and he would point those rafters out to visitors.

The second indication that this organization was serious business was the informal mission and vision statement of Ecosense, the one emblazoned on the wall right behind the reception desk, right under the stylized logo and the word Ecosense. That mission statement was, “To fight the pagan death cult until we hang their last dog.