Introduction

The next time you find yourself in need of a deeply unsettling experience, I suggest that you click here, and then scroll through some of the things that Dylan Curran found out about himself, as stored up by some of our brainier brethren. All the same stuff has no doubt been stored up about you. And although the experience of considering such things is deeply unsettling, handled the right way it can become deeply edifying as well. But for the edifying part, you will have to read all the way through.

Privacy or Anonymity?

We live increasingly in a surveillance state. Cameras are everywhere—pointing at intersections and pointing at 7-11 counters. Some of it is reasonable security, some of it is officious meddling, some of it is counterproductive, and some of it is creepy. What I would like to do here is separate the creepy from the rest, and then make a suggestion as to what we might be able to do about it.

No one faults a small business owner for having security cameras. Entirely reasonable. But the practice of handing out traffic tickets on the basis of intersection cameras has to be reckoned as counterproductive. Notice that traffic tickets have ceased being a way of keeping the public safe and have instead become a cash cow for the budget of the department in question. We have managed to incentivize things the wrong way—instead of officials hoping for no lawbreaking at that intersection, it would now be good for their bottom line if there were an increase of lawbreaking at that intersection. Perverse incentives.

The creepy is something we know instinctively, but even here we haven’t sorted through the issues carefully. We think we are prizing our privacy, but what we are actually doing is striving for anonymity. Privacy requires a public face, while anonymity requires far more than any sinner should ever think to require.

A man who walks down Main Street is entitled to his privacy, but the fact remains that everybody can see him. His privacy is a public fact, and we may leave him to his own affairs. But when we do so, we still know his name.

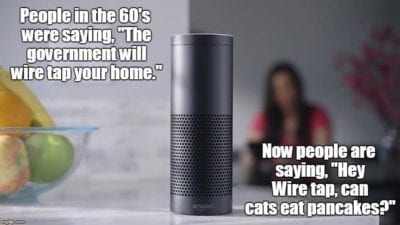

A man who travels all over the country with his location services turned on the whole time should not be surprised if some flunky over at Big Data can reconstruct his whole trip for him. He should have known, in other words—from the basic facts of the case—that he was walking down Main Street. But a man has every right to be surprised (and dismayed) to find that his camera and microphone were active the whole time, recording way more than he expected.

Issues of Competence

We are not just dealing with a (plausible to us) attempt at omniscience, we are also dealing with finitude (tiny omniscience) and sinfulness (dirty omniscience). On top of that, we are also dealing with arrogance (the-kind-that-goeth-before-the-fall omniscience).

Here is something C.S. Lewis said about human knowledge in his discussion of historicism.

“It is not a question of failing to know everything: it is a question (at least as regards quantity) of knowing next to nothing. Each of us finds that in his own life every moment of time is completely filled. He is bombarded every second by sensations, emotions, thoughts, which he cannot attend to for multitude, and nine tenths of which he must simply ignore. A single second of lived time contains more than can be recorded. And every second of past time has been like that for every man that ever lived” (C.S. Lewis, Essay Collection, “Historicism,” p. 627).

The accumulation of massive amounts of data on you is an optical illusion. When someone on the other side of the country can tell you how many steps you took in a day, and what side of the street those steps were on, this creates an artificial resemblance to the kind of knowledge that God has. But this resemblance is illusory, a sham, a lie.

God knows it all. His knowledge is immediate. He knows the context perfectly. He is holy and without sin. He is a loving Father.

But if Googlemen were to crack open your file, they have far more information on you than they can understand. They have to treat that file as a quarry from which they might select facts on you (whether they want those facts to be exculpatory or damning depends on the situation). But they will have to select and ignore, and they will have a particular standard of selection. And that is where I will ask my favorite question. By what standard?

These men know (and can prove) that Mr. Jones, from his place of work, accessed a website (let us call it Bikini Bimbos.com), and was on that web site for 45 seconds. And so the data wonk says, “J’accuse.” Left out is the fact that he did so because Mrs. Jones, having just caught their Billy on the same site at their home computer, called her husband, and asked him to see how bad it was. Or contrariwise, remembering the condition our world is in, Mr. Jones might have just been sinning. The point is that God knows, and that Google doesn’t.

Toward a Christian Response

I suspect that all of us will have an increasing number of occasions where we have to talk about such things, and I also suspect I will have a great deal more to say about it. What I want to do here is simply sketch the beginning of what I think should be a biblical response.

We must begin with the assumption that digital condemnation of any man should be out of court. Digital information is highly susceptible to manipulation, and digital information is highly portable. I believe that we should begin the fight to outlaw all such information in court, and we should lead by courteously disbelieving any report made against anyone on the basis of what somebody “found on their computer.”

“But he that is spiritual judgeth all things, yet he himself is judged of no man. For who hath known the mind of the Lord, that he may instruct him? But we have the mind of Christ” (1 Cor. 2:15–16).

In the old days, if the cops found a warrant for a man’s arrest, and they showed up at his house, and they found the basement full of child porn magazines, this was a scenario in which the biblical standards of evidence could be met (multiple witnesses, etc.). But if the agents cart off his computer, and then late that night down at the station, they “find” child porn, there are too many problems. Was the porn actually there (as it often is), so guilty as charged? Was it placed on the computer via a thumb drive after the arrest? Was it planted on the computer by that man’s enemy before he placed the phone call that led to the request for the warrant?

As a corollary, we should also be extremely skeptical about claims and accusations made on the basis of this kind of thing. This is not because such charges couldn’t be true. They frequently are true. But rather I say this because the common man’s ability to protect himself against framing allegations has not yet caught up with a malevolent person’s ability to accuse.

Power corrupts, and digital power is certainly power. The companies that traffic in this kind of data are vulnerable themselves—one scandal too many, one hack to many, one data loss fiasco too many—and they might find themselves losing out to their competitors. The best thing we can do in this area is to support deregulation of the tech industry, making it easier for new companies (that advertise “we don’t keep your info” as a selling point) to compete with the giants.

Conclusion

It remains the case that God is not mocked. It remains true that you reap what you sow. We can therefore be assured that when the creepy aspects of this new era get themselves sorted out, we will still be living in a world that is governed the way God wants to govern it.

In the meantime, we should be more suspicious of accusation than we are. Call it a good starting point for our operation stance. Lord willing, I will have a good bit more to say about all this.