Introduction

Since discussions of Christian Nationalism are now officially a thing, I want to make sure that I do not shirk when it comes to any responsibility I might have to help make the case. So, how about this?

“For the nation and kingdom that will not serve thee shall perish; Yea, those nations shall be utterly wasted.”Isaiah 60:12 (KJV)

I love my nation, and do not want to see it utterly wasted. I am therefore engaged in the task of inviting my fellow Americans to make the choice of “serving Him.” The nation that will not serve Him shall . . . perish. We don’t want that, and so certain things follow.

People Complain That Nobody Knows What It Is

One of the complaints about CN that I have heard oft repeated is that nobody knows what it is exactly. “I have heard about 57 different things concerning it, and so I don’t know what to think anymore.” Yeah, but about 54 of those different versions came from die hard opponents freaking out about “the very idea,” whereupon they began circulating misrepresentations, lies, mendacious interpretations, and scurrilous abuse. Christian nationalism wants to outlaw sin? Gee, why didn’t anybody think of fixing the world that way before?

If you want to know the range of proposals coming from advocates of the idea, then read three books: Christian Nationalism (Torba/Isker), The Case for Christian Nationalism (Wolfe), and Mere Christendom (Wilson). That will give you the lay of the land, and it will also give you a sense of some of the intramural differences. There are some differences, but nothing that affects the central idea. And here is the central idea, the basic thrust. Our dalliance with secularism has proven itself to be flat out bankrupt, and so we need to turn in repentance back to the Christian foundations that our nation was established on.

Gross distortions of what is being said should just be wadded up and tossed aside. We are not envisioning Kim Jong Un’s North Korea, only with Bible verses attached. We are rather thinking of something more like the civic arrangements recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1892. You know, that hellhole. The next rainy Saturday you have, you should go up into your attic, open that trunk of remembrance, and look at your great-great-grandmother’s red handmaid dress, and whisper never again to yourself.

So dishonest questions just stay slippery and move over to some other comment thread. Honest questions can be handled with honest dispatch.

Speaking of Honest Differences

John MacArthur was recently asked about Christian Nationalism, and his reply was two-fold. First, because of his belief about the nature of the church, he said there was no such thing as Christian nationalism—the kingdom does not advance “in that way.” Second, because of his rejection of postmillennialism, he in effect says everything is going to get “worse and worse,” and that we are going to lose down here.

With regard to this second point, it gives me a great deal of pleasure to observe that in the recent COVID hysterics, John MacArthur was one of the few courageous stand-out pastors who didn’t lose down here. It must have been really disorienting. As Ransom said to Jane, speaking of MacPhee, “You couldn’t have a better man at your side in a losing battle. What he’ll do if we win, I can’t imagine.”

With regard to his first point about the nature of the church, I would simply want to point to a number of events in church/state history, events that I believe MacArthur himself would recognize as resulting in great blessing for God’s people. When Frederick the Wise protected Luther, did that result in any true blessing for the church? When evangelical pressure on Parliament enabled Wilberforce to require the East India Company to open India up to missionaries, what was that? And when Constantine put an end to the public sacrifices to the pagan gods, wasn’t that a good thing?

Then There Is the Logic of the Thing

Other objections should be addressed because keeping faith and political issues separate is not really possible. In this section, I want to address the structural problems with how some objections to CN are framed.

Like that oft-repeated phrase, separation of church and state. It is certainly possible (and desirable) to keep church and state separate. This is because church and state are both governments or institutions. They have different jurisdictions which can and should be kept apart. It is possible to keep the apples and oranges separate because they are both fruit, and you have two bowls right there on the counter. So simply do it. Separate them.

But the confusion that swirls around the phrase “separation of church and state” represents a monumental category confusion. You can separate church and state because they are both distinct forms for human governance, just like apples and oranges are both different kinds of fruit. So separate them. But if you have come to believe that this means that you can separate morality and state, or the one true God and state, or forgiveness and state, then you are begging for tyrannical chaos. And look . . . that’s just what we have been getting.

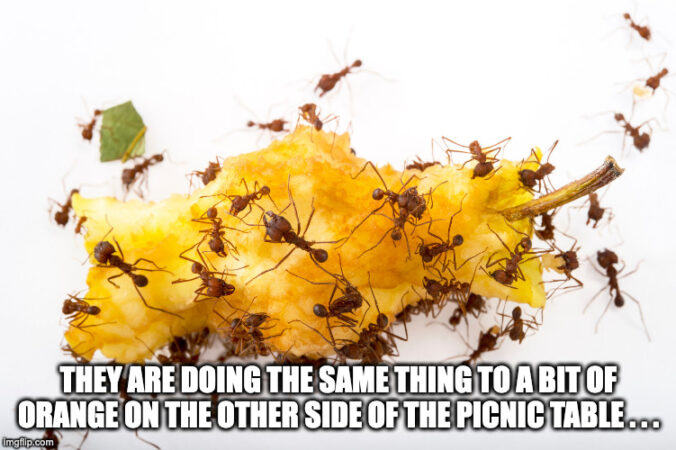

Think about it for a moment. Under the spell of this confusion, you are not separating apples and oranges, but rather freshness and apples. Think for another moment. Do you really want to separate morality and state? Do you really want a state that is freed from all moral considerations whatever? Now you have withered apples with ants crawling all over them. Separating oranges from apples keeps the produce section of Safeway from descending into chaos. Separating freshness from apples means that we wouldn’t want to have anything to do with apples. Separate morality and state? Really?

Inescapable Concepts

But if you don’t separate morality and state, then you run smack into the inescapable question . . . which morality? This is one of those inescapable concepts—not whether, but which. Not whether morality, but which morality? All laws are imposed morality. I will say it again. All laws are imposed morality. And all moralities arise out of a moral system, most of which are religions. And the moral system of secularism, while not a religion proper, is every bit as religious, and authoritarian, and coercive, as sharia law is.

You question that? The secularists will allow a surgeon to cut off a young girl’s breasts, and they will also revoke parental rights if the parents try to stop it. They are imposing their morality on the parents. Are they not? And if a preacher rises to condemn it, as he should, when he gets to the “thou shalt not” part, he will be interrupted. The question will naturally be, “Who says we may not do this thing?” And the only possible answer that a Christian minister may give is “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the great God who spoke to Moses on the mountain, and the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. He says.”

Without a coherent, unified moral system that undergirds her laws, a nation cannot exist as a nation. Unified law requires moral consensus, and moral consensus requires a shared system of values. What I am saying here is that I don’t believe that this system of values should be wrong from top to bottom. I believe that the morality we base our laws on should be correct, and not twisted or demented. And that requires us—as a nation—to answer the question, “by what standard?”

If the answer to that question is supplied by a cacophony of voices, then you are going to get cacophony in the laws, and shortly after that, cacophony in the streets. What about the last five years would make anyone think that this reasoning was wrong?

One Last Worry

The Christian faith is deep within the American DNA. So is Calvinism, and so is postmillennialism, but that is a topic for another time. It is nevertheless down in our bones. I am a Christian, and a Calvinist, and a postmillennialist, so all of that works out quite conveniently for me. I believe there is something deep within the American psyche that postmill Calvinists can appeal to, and so that is a task that is conducive to me because I believe it to be the truth of Scripture as well.

But I am not a baptist, and the baptist ethos is almost as deeply embedded as the Calvinism and the postmillennialism. So if as a Presbyterian I am making an appeal for Christian Nationalism to a nation that has been profoundly shaped by the baptistic ethos, this is something that I must respect and take into account. Baptistic excesses, like a too great emphasis on individualism, should be guarded against while at the same time respecting baptist contributions and cautions.

Baptists have long memories, and in post-Reformation history, there have been times of inter-denominational persecution. Baptists remember all of that, and don’t want anything like it again. They don’t want the Presbyterians to take over, and put out a warrant for James White’s arrest. Now I believe the odds of someone like James getting arrested for wrongthink are way higher in the present moment than it would be if we were in charge. If we were in charge, he wouldn’t even get in trouble for those coogi sweaters he wears. I mean, it would be a free country, even though some people might be pushing the limits.

So however unrealistic I think this worry might be, and I do, the concern cannot just be waved off. It should be answered. And here is that answer, and it is an answer that goes to the root of the thing. If the Presbyterians fulfilled every Baptist’s nightmare, and started in with denominational persecution, would that be a violation of what Jesus would want us to be doing in the civic realm? If it would be—and we agree that it would be—I would then ask, “Should we modify our behavior down here to conform to what the Lord wants?”

And if the Baptist answers yes, as he should, then I would say, “Welcome to Christian Nationalism.”