Introduction

So I have been going on for some years now, or maybe a decade or two, about the prospect of a mere Christendom. A few years ago it all seemed pretty radical, but as time wears on, and as our mainstream corridors of power seem incapable of producing anything other than Bad Ideas and Balrogs, the idea of a mere Christendom has started to look more and more alluring. At least to sensible people.

That being the case, I thought this would be a good time to explain how the idea of mere Christendom is not some theosyncratic idea of mine. It comes from the Reformed mainstream, and for most American Presbyterians, it is a confessional issue. I will explain that further in a moment, but in the meantime the fact that almost no one thinks of it as a confessional issue is a plain demonstration of how the spirit of soft postmodernism has taken over the ostensibly Reformed bodies of North America.

Richard Rorty summed it up this attitude nicely when he said, ““Truth is what your contemporaries let you get away with.” Any ordained minister in the OPC or the PCA—or in any of the smaller Reformed bodies for that matter—who disagrees with the concept of mere Christendom really is obliged in simple honesty to take an exception to the American version of the Westminster Confession at this point. Honest subscription needs to require this because no one else will require it. This is because confessional truth has become what the presbyteries will let you get away with.

And on this topic—and it is not the only one—the answer is “quite a lot,” as it turns out.

Show Outline with LinksAn American Take on Christendom

The Presbyterians in America held their first general assembly in Philadelphia in 1789. Perhaps that city and that year should ring a bell for you, and at that assembly they adopted an American version of the Westminster Confession. One of the places where they altered the original Westminster Confession, in this case improving it, was the chapter on the civil magistrate.

The original Westminster was drafted in a context where there was an established state church already, and the contest between Anglicans and Presbyterians was over what form that established state church should take. So the original Westminster was decidedly Christian on this point, assuming an established Church, but that original Westminster was also Erastian, which was a problem. Erastianism means that the civil ruler has final authority over the church. Not a good idea.

This is the language of the original Westminster:

“The civil magistrate may not assume to himself the administration of the Word and sacraments, or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven: yet he hath authority, and it is his duty, to take order that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire, that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed, all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented or reformed, and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administered, and observed, (Isa 49:23; Psa 122:9; Ezr 7:23, 25-28; Lev 24:16; Deu 13:5-6, 12; 2Ki 18:4; 1Ch 13:1-9; 2Ch 34:33; 2Ch 15:12-13). For the better effecting whereof, he hath power to call synods, to be present at them, and to provide that whatsoever is transacted in them be according to the mind of God.”

WCF 23.3

The glaring problem here is that the magistrate not only has the power to convene synods, and to be present at them, which would be fine, but also to determine whether or not all those ministers and theologians were reading their Bibles right. This grants the magistrate far more authority in sacred things (in sacris) than he really ought to have. He does have necessary authority around sacred things (circa sacra), which is why he should have the power to convene synods and to attend them. But he really should not have the power to dictate to the church what the “right theological answer” ought to be.

Because we here at Christ Church subscribe to the original Westminster, we take an exception at this point. On this issue the American Westminster is an improvement, although as we shall see, it has an imperfection of its own.

And so what does the American Westminster call for? Well, in brief, it calls for a mere Christendom.

“Civil magistrates may not assume to themselves the administration of the Word and sacraments; or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven; or, in the least, interfere in matters of faith. Yet, as nursing fathers, it is the duty of civil magistrates to protect the Church of our common Lord, without giving the preference to any denomination of Christians above the rest, in such a manner that all ecclesiastical persons whatever shall enjoy the full, free, and unquestioned liberty of discharging every part of their sacred functions, without violence or danger. And, as Jesus Christ hath appointed a regular government and discipline in his Church, no law of any commonwealth should interfere with, let, or hinder, the due exercise thereof, among the voluntary members of any denomination of Christians, according to their own profession and belief. It is the duty of civil magistrates to protect the person and good name of all their people, in such an effectual manner as that no person be suffered, either upon pretence of religion or of infidelity, to offer any indignity, violence, abuse, or injury to any other person whatsoever: and to take order, that all religious and ecclesiastical assemblies be held without molestation or disturbance.”

American WCF 23.3

When I wrote about this on another occasion, I said this:

“Both forms of the Confession acknowledge that the magistrate has authority circa sacra, around sacred things, and both deny that he has authority in sacris, in sacred things. I want to argue that both are basically Kuyperian, although they are obviously leaning in different directions. We might struggle with the original Confession, where it says that the magistrate has the authority to determine that decisions by church synods are in conformity with the Word of God. How is that not taking away with an Erastian hand what was given to the Church earlier in the paragraph with a Kuyperian hand? But we should also have trouble with the American version, where it says that the magistrate cannot interfere with matters of faith “in the least.” How is that not sowing the seeds of a latter departure of the civil magistrate from any duty to Christ whatever?

Me, here

But let’s be charitable. That troublesome phrase “in the least” could easily admit of quite responsible interpretations, and which, at the time it was written, it probably did. But it was kind of like the “general welfare” clause in the Constitution, a little frayed spot in the knitting which the bad guys could then pick at until they had pulled the whole sweater apart.

So let us set aside that “in the least” for a moment. I take it as saying that the magistrate must not interfere in sacris at all. But in the American version, what may the magistrate do? When it comes to circa sacra, he has quite a bit of scope, and it is a scope that presupposes a mere Christendom. Notice how the whole thing is framed with regard to the civil magistrate’s relationship to various denominations of Christians.

Civil magistrates are to be Isaiah’s “nursing fathers” to the church, meaning that they are to be truly supportive of Christian churches because they are Christian churches. They would not be nursing fathers to synagogues or mosques. The magistrate has a duty to “protect the Church of our common Lord, without giving the preference to any denomination of Christians above the rest.” In other words, the American Confession states, as a confessional matter, that the magistrate should be uniquely protective of Baptists, Anglicans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists, and including in that list any other body that can lay claim to being a church that belongs to our “common Lord.” This is mere Christendom. It is a Christendom that sidesteps the question of whether a particular denomination should be established as THE official church of the republic. It should not. A major part of the magistrate’s duty is to leave all Christian leaders in untrammeled liberty, free to pursue any part of their ” sacred functions” without threat of violence or danger. All Christian bodies should be free to worship God according to the dictates of their conscience and their understanding of what God requires of them. The worship of our common Lord was to be conducted hassle-free by all, and with the sure knowledge that magistrate was not going to be antagonistic.

It would be an error to assume that this meant that these worthy Presbyterians believed that Jews or Muslims ought to be persecuted. I don’t think that this is an implication of their words at all. But it is certainly to say that the Christian faith would get preferential treatment (nursing fathers) and encouragement.Two Approaches to Mere Christendom

There are two ways to approach the formation of mere Christendom. Both of them are fine, but I do have a preference for the second one, for reasons that I hope will become obvious.

When the Constitution was put together (also in Philadelphia right around the same time that the Presbyterians were there), and was later ratified by the 13 states, it is striking that 9 of the 13 had established state churches at the state level. Connecticut kept her state church (the Congregational Church) down into the 1830’s. This is one approach to mere Christendom, the one I am less enthusiastic about. A national body like the United States did not have a national church, not because we were anti-Christian, but rather because we were a federation of states, and each of those states had the option of establishing a church. If a state has a state bird, or a state flower, or a state anthem, and the national government has a national bird, or a national flower, or a national anthem, it is unlikely that any serious conflict will arise out of that. But if a state establishes the Presbyterian church, and the national government picks the Episcopalian church instead, then you are just asking for conflict. And so the Founders said that there would be no Church of the United States, the way there is a Church of Denmark or a Church of England. So this means that if Idaho established a Christian denomination as the official church of Idaho, there are any number of arguments that could be brought against the move, and I myself would bring a number of them. But one argument I would not bring, and that is the argument that to do this would be “unconstitutional.” It would be nothing of the kind.

The second approach is what might be called “informal establishment,” and is an arrangement that is very much like what is described in the American Westminster 23.3. This was what America functionally had, from the Founding down to the early part of the 20th century. But in order for it to work, there had to be a widespread Christian consensus. As long as that was there, an informal arrangement could work. When it started to erode, as it has massively over the last half century, the secularists can immediately place all “religions” on the same footing—from Methodism to Melanesian frog worship, from jihadis to Jehovah’s Witnesses, from Baptists to Balrogs—in order to observe cynically that there is clearly no common denominator tying all these together, and so we will have to go with a “neutral” secularism instead. But secularism is a faith-system, just like the others, and has absolutely no claim to a privileged position.

We have two reasons to hope for a return to a Christian consensus, of a kind that could support a mere Christendom again. The first is our hope and prayer that God will grant reformation and revival to His church. The last several years have revealed that large sectors of the church were just playing games, but it has also been encouraging to see that there are many believers who really mean it. May God restore His church, empowering it, setting it on fire.

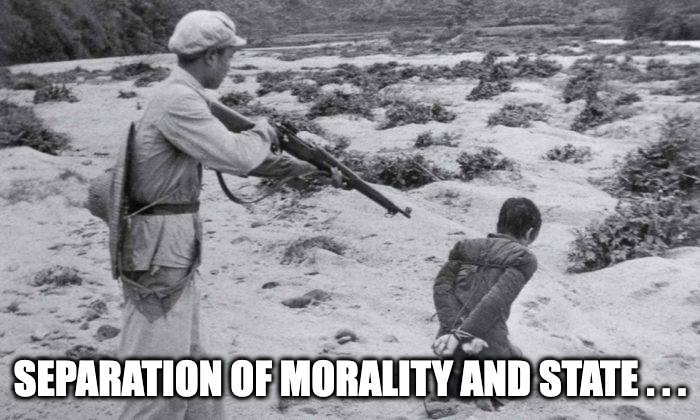

Speaking of fires, that is the second reason for hope. Secularism has turned into a huge dumpster fire, the kind that happens behind a restaurant that cooks with lots of grease, and I don’t see how they can recover. The thing they had going for them was that they used to be able to say to gullible Christians something like, “You see, we can be decent and moral, just like you religious people. We share the same common values, only we don’t appeal to a transcendental reality to ground those values. We can be trusted to be neutral referees when it comes to what we all share together as decent, law-abiding Americans.”

That used to fly. That used to work. But that was before 60 million children lost their lives. That was before Planned Parenthood started selling the baby parts. That was before drag queen story hours at your local library. That was before doctors started taking money to conduct mastectomies on healthy young girls who had been hectored into thinking they were boys. That was before the lockdowns, and the masking orders, and the mandatory vaccine orders. In short, that was before somebody unlocked all the cages in the monkey house, and told all the monkeys to go conduct their poo fights in the public square.

When that kind of diseased secularism finally ascends to the sky in a column of greasy, black smoke, I believe there will still be the remains of a Christian consensus that we can appeal to. What we need are a sufficient number of Christian leaders who will be unafraid to challenge the dogmas of neutrality. I believe that when the insanity passes, as it has to, there will be many millions who are hungry for a sure word from God.