The small boy stopped and chunked some dirt clods at the fence post. Ten throws, six hits. Better than yesterday.

Dave turned homeward again, pack over his shoulder. Coming around a corner, he saw the house down at the end of the dirt lane, about half a mile away. The road sloped gradually down for about two-thirds of that distance, and then rose again to the house. On either side of the lane were meadows and pastures, randomly placed. Most contained cattle, grazing off away from the road, over by the tree line. Without thinking about it, he began to trot. Mom would have milk and something out of the oven, and they would talk. He didn’t put it to himself like that, but he did enjoy coming in the back screen door and slamming it. Mom always knew who it was, but she would always say, “Who’s that?”

This late September hadn’t seen rain for weeks. Little puffs of dust exploded where his feet hit. He was running with his head down, watching them go off. Foot grenades. Foot grenades. Wait. The old elm was coming up. He would have to stop for a minute and throw rocks at it. He slowed down and started looking around for rocks, trying to remember yesterday’s record, but was quickly distracted by a large stick instead. Dave picked it up and hefted it in his hands, pleased with his new broad-sword.

He went on at a walk, every few steps mowing down the tall grass growing in the ditch at the right side of the road. A blue jay flew by, landed on a fence post about twenty feet ahead, and decided to leave again as Dave approached, whacking as he came.

This morning his mother had said it was a glorious day. Mom always talked like that. Dave thought it was nice, too. He’d gotten a 92 on his math test. All that drilling last night worked. She’d be really happy about that. Before dad went to fight in Korea he had said that Dave was supposed to work hard at his studies. Maybe mom could put something in a letter about it.

A cloud went in front of the sun. Dave looked up. The sun would be back out in a minute. He stood still in the road, watching the cloud. He wanted to be a pilot. The cloud moved on, and the sun hit him full in the face. Dave shut his eyes, but remained still as he felt the autumn heat. It was different than summer. With his eyes still shut, he took a few more steps down the road.

“Hey!”

Dave stopped and looked down, opening his eyes.

Another boy was by the side of the road. He was standing next to a driveway that led off to the right, between two fenced-off meadows, presumably back to a house in the trees. Dave thought he was about two years older, and twenty pounds heavier. They both stood still for a moment watching each other, sizing one another up.

“You’re new here.” No question, just a statement.

Dave nodded and swallowed. The other kid was not standing the way new friends stand.

“Hi,” Dave said.

The other boy ignored his greeting. “What do you think you’re doing, walking off with my stick?”

Dave looked down at the stick in his hands. “I didn’t know,” he said. “Here.” He extended it to the boy, who knocked it out of his hands. He swallowed again. He didn’t know what to do, and he knew he was going to have to decide what he was going to do.

The other boy took a step toward him. “I’ll pound your face into a jam pudding. That would be just fine with you, wouldn’t it?”

“No,” Dave replied. But he was mortified because his voice quavered.

“That’s too bad, because that’s what gonna happen.”

Dave glanced down the road at his house. It was a hundred miles away. The other boy took another step closer and then lunged. Dave dodged and ran past him. The boy grabbed at his sweater but missed. After a brief but hot chase, it was clear that Dave was faster, even with his pack of books. The other boy stopped. Dave slowed to a walk and continued on.

The other boy shouted after him. “Yah! I bet you know how to run!”

Dave walked on, miserable. That wasn’t the right thing. That wasn’t the right thing to do.

He looked back and saw that the boy had returned to his place by his driveway. He was just standing there. Dad said I had to stand up to bullies. That kid is big. I have to walk past here every day.

Dave went over to the side of the road, a different kind of miserable. He put his book pack carefully down and rubbed the palms of his hands on his trousers. He bent down and adjusted the straps on the pack, just for something to do while he thought for a minute. Then. with a deep breath, he turned and walked slowly back up the road.

The other kid was startled, or at least Dave thought he was when he was thinking about everything later. But he really didn’t have time to think or notice.

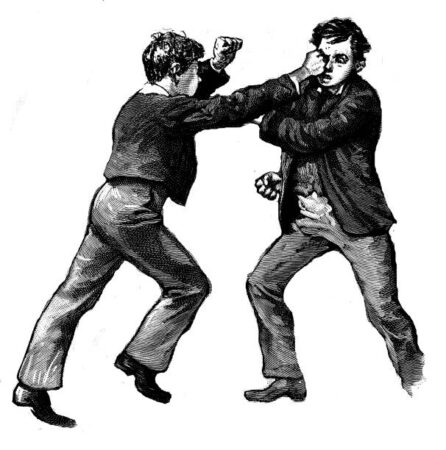

No sense in talking, he thought. So when he got within about ten feet of the other boy, he put his head down and ran straight at him. This was his first fight and he wasn’t sure of everything he was supposed to do. But his fists were clenched, and when he saw the other boy’s feet he swung his arm up over his head and down. The unorthodox approach left the other boy not knowing how to defend himself.

So the fight began with a bit of good luck. Dave’s first blow landed squarely on the bridge of the other boy’s nose, resulting in a spectacular nose bleed. They grappled for a moment, and then came apart. Dave saw the damage he had done, took courage, and charged again. This time the other was ready and punched Dave in the mouth, knocking him down. Dave was a very quick boy and was back on his feet immediately. He was completely astonished at how little the blow had hurt. This isn’t so bad, he thought, laughed out loud, and charged again.

Dave did not see it, but this time the surprise on the face of the other boy turned a little anxious. He was a successful bully, and, like many bullies, he had not had tn do very much actual fighting. Taunting and bluffing, delivered with enough verbal force, usually got him what he wanted.

It had worked the first time, so Dave charged with his head down again. This time he didn’t swing at all. With the top of his head he rammed into the other boy’s jaw, causing him to bite his tongue. The bully took a step backward, with his hand to his mouth. Dave continued to run at him, throwing his fists as he came. Many of his punches just provided for a visual effect, but a surprising number of them landed.

The other boy tried to run backward, but tripped and fell. Dave jumped on his chest and continued to throw punches. The other tried, unsuccessfully, to return the fire, but he could not punch lying on his back. The spirit of battle was now completely on Dave, and he had no intention of stopping. His fists were now connecting to the other’s head, hard at every blow.

“Uncle!” the boy roared.

Dave laughed, and said, “Say ‘jam pudding.’”

The boy shook his head, and started to cry, so Dave hit him again.

“I said to say ‘jam pudding!’”

The boy mumbled something which sounded like it might have been “jam pudding,” so Dave got up and backed away. The other boy slowly stood up, glared at Dave, turned and ran up his driveway, reporting the crime to his mother in a loud voice.

Dave walked slowly toward his house, filled with elation. He felt his mouth full of something else, something warm. He spit, and saw the blood hit the dirt road. I bet Dad knows what that looks like.

He grinned happily. Victory.

She had seen him come around the corner at the top of the lane. The bus was very predictable, and she would always go to the bay window at 3:45 to watch him come around the bend. It used to delight her to see how long it took him every day to make the half mile. She knew many of his little routines almost as well as he did.

Today she came to the window a few minutes late, just in time to see the last encounter between the two boys, just before Dave ran way. Oh no, she thought, and then she gasped with relief when she saw her son take flight. She headed toward the door, and then stopped, filled with a maternal horror. Dave was putting down his books and walking back up the road. She moved quickly to the front door, opened it, and walked out on to the front porch.

What had John said? They had talked about this before he had left. Her hand was at her mouth, and she felt the fear rising up from inside her. They had talked about that too.

She stood and watched Dave’s first charge, and then, slowly, deliberately, obeying her husband, she sat down on the top and watched. She had a husband fighting in Korea, and a son fighting the down road.

It was hard to make out what was happening from this distance, but she knew Dave had the blue sweater on. When he was knocked down, she stood up and then sat down again. The fear was in her mouth, so she swallowed.

Every day she walked by this place. Every day the fear came out and taunted her. Is John safe? It did not matter where she was, or what she was doing. Every day she came by this place. I need to take a lesson from my son.

She just sat on the step and watched. By now the fight was almost over. No longer concerned for his safety, she now began to worry about his conscience. The blue sweater was sitting on top of the other boy, flailing at him. She stood up and then sat down again.

When she thought about it later, she wasn’t sure what happened to her there on the front porch. She tried to explain it in a letter to John a few weeks later, but was not really sure she had explained it well. But deep inside her, she had let it go.

The fighting boys detached, and she saw the other child running up his drive. She could hear his yelling. faint but audible. The blue sweater had returned to his books, picked them up, and was walking slowing toward her.

She sat for a few moments, and then she smiled wearily. Victory.

In the other room, the phone rang.