Introduction

In conservative Christian circles, worldview thinking was quite a hot item for a while. Most recently, I reckon it became “a thing” among us during the Francis Schaeffer times, and it then burgeoned into something of an industry. In North American circles, the kick-off was Schaeffer’s How Shall We Then Live?—the book and film series both. There were worldview summer camps for teens, and there were series of books published addressing all manner of subjects in the “light of a Christian worldview.” My book Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning was part of the Turning Point series, for example, a series that was right in the middle of all of this. And organizations like the Nehemiah Institute even developed a test that would evaluate the extent of your worldview soundness.

Of course, the idea of worldview didn’t begin in the seventies—we should also mention luminaries from previous centuries such as Kuyper, Bavinck, and Orr. And the thing itself has appeared in various places, although not necessarily by that name. For example, Owen Barfield once said of Lewis that what he thought about everything was contained in what he said about anything, and it is hard for me to imagine a better definition than that of worldview thinking. Worldview thinking is nothing more than thinking and believing as a whole person. It is to have an integrated intellectual life, instead of having an intellectual life that is scattered around the attic in bits and pieces.

But There Have Been Critics . . .

Back in the days of The Calvinist International, the idea of worldview thinking was found wanting. A recent book, Against Worldview, by Simon Kennedy, has made this sentiment clear enough. To be fair, Kennedy’s approach appears to want to build out a more robust form of worldview thinking, while avoiding a truncated or superficial approach. And Stephen Wolfe has also been critical of the worldview approach, arguing that it makes pastors feel some kind of pressure to be an authority on everything, leading to unfortunate results. Unfortunate results have really happened in various places, by the way.

The Problem of Jargon

So it should be granted at the outset that whenever any intellectual movement becomes popular, as worldview thinking most certainly did, this means that a bunch of people will adopt it. And when you have a large number of people doing anything, they will bring the bell curve with them. The bulk of them will profit by it, gaining something from it. A handful on the right end will become Jedi masters, while a number of folks on the other end will fold the jargon of the movement into a paper hat, and right after they don the hat, they will stand up straight and proud in order to offer seminars.

But this difficulty is not a worldview thinking phenomenon, it is a human being problem. After some business guru holds a training seminar for your company that manufactures widgets, there will be somebody in marketing talking about developing a new paradiggem that will enable the company to move into the future, while at the same time optimizing outcomes and achieving synchronicity with all co-creators. This will happen whether or not the initial business guru was making any sense or not. This happens everywhere and with everything, in other words.

So if something like “biblical wisdom” catches on, instead of worldview thinking, then there will be lame adherents of that approach who would make it easy to pick them off as the straw men representing that view. Straw men are frequently not imaginary men, but rather are the least capable men in any movement. But picking off the stragglers is not the way to critique anything. That is not the way. This is because if the most capable men in these movements were to get together to discuss it, they would soon discover that their differences were semantic. And because none of them want to be accused of being anti-Semantic, they could soon come to agreement.

Now of course, the less capable men don’t care about being accused of being anti-Semantic, but that is another story. Samuel Holden could make a video filled with white boy malapropisms, and they would think it was marvelous. But let us not get derailed.

The Necessity of Integration

When Logos School was first founded, one of our central mission goals was to “teach all subjects as parts of an integrated whole, with Scriptures at the center.” I think it would be difficult to come up with a more concise statement describing what worldview thinking is. As Cornelius Van Til once put it, the Scriptures are authoritative in all they address, and they address everything.

And of course Scripture addresses everything at the root, and not at the twigs. The Bible doesn’t speak directly about computer fraud, or online porn, or the godly way to maintain jet turbines, or dishwasher repair. The Bible is not a DIY YouTube video. But there is nevertheless a biblical way to think about all such things. The Bible addresses everything in principle.

In Screwtape, the junior devil is told that “your man is accustomed to have a dozen incompatible ideas dancing around in his head.” But this condition of having a confused intellectual jumble up there is only a temporary transitional thing, Man being what he is, there will always have to be a principle of integration somehow, somewhere. As Dylan once put it, “it may be the devil, or it may be the Lord but you’re going to have to serve somebody.”

If the principle of integration is not Christ and His Word, then it going to be something else. It might be a bottle of red pills. It might be the color of your skin. It might be the fact that all your academic colleagues voted for Harris and you didn’t want to feel left out. It might be the desire to be an authority on hot Indy bands, But one way or another, it is eventually going to come down to a binary choice—either the Word or the world, And those who make friends with the world are making themselves enemies of God (Jas. 4:4).

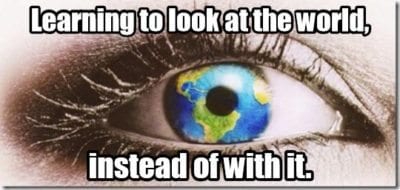

If you don’t learn how to look at the entire world with a biblical eye, you will soon find yourself looking at the entire Bible with a worldly eye. One or the other,

A Wheel, Not a Pogo Stick

Where worldview thinking has frequently gone astray is in the same place that catechism instruction has. You teach the questions and answers, and the student is thereby equipped with ready made Pat Answers. Everything reduces to mere propositions, and all without application. Say the right things whenever anyone puts the quarter in. This error is made much more likely if people are taught that worldview thinking is limited to thinking.

I have sought to address this error in my little booklet A Worldview Wheel. Instead of jumping up and down on the pogo stick of propositions, I argue that a Christian worldview is actually a wheel with four spokes, two of them propositional, and two of them enacted. The axle is the grace of God, and rim of the wheel is the Lordship of Christ over everything.

The two propositional spokes are Catechesis and Narrative. Catechesis is the doctrine, the teaching, the propositions that we affirm as Christians, while Narrative is the story that we tell about our origins, our history, our place and our destination—who are we, and where are we going?

The two enacted spokes are Lifestyle and Ritual. Lifestyle addresses how we actually live, work, marry, travel, water the garden, and so on, This is an embodied spoke. And Ritual has worship at the center, of course, but it also includes all the lesser rituals, from the Pledge of Allegiance down to the seventh inning stretch at the ball game.

So it should be noted that absolutely everything we say, do, or think can be grouped under at least one of these four categories. Nothing is left out, nothing is excluded. They are all set in the axle of God’s goodness to us in Christ, and the end result is that we roll along nicely,

The Pastor as General Practitioner

And this is why a pastor must be a specialist in the Scriptures, and also a generalist when it comes to the rest of life. As John Stott argued in Between Two Worlds, a minister must study the Word and he must also study the people that he is ministering to. His task is to communicate the constant message of the Word to people who inhabit the inconstant world as it currently is.

Contra Wolfe’s criticism, the pastor does not have to be an expert on everything, which would be impossible. He cannot be a specialist in everything. But he must be a generalist in order to shepherd the flock. They are going to come to him with very practical questions, some of them pretty thorny, on subjects that weren’t covered in seminary. Is it lawful to join the military? Does it matter who the president is? How do we go about understanding medical technology and end-of-life care? Is it a sin to be addicted to sleep meds? We have a homosexual son far away from the Lord, and should this affect his inheritance? I have been accepted into a PhD program in geology, and I need to get straight on the age of the earth as I consider it.

There is no way to be faithfully trained in the Scriptures without coming into sharp collision with secular experts in varied fields, such as psychology, astronomy, geology, history, economics, philosophy, and all the rest. There is mind/body issue, the age of starlight, the fossil residue of Noah’s flood, the long day at Aijalon, the propriety of watering down the wine, and the vain deceit Paul warned about. The Bible is not hermetically sealed off from the world in which we must obey the Bible. And that means that a worldview approach is necessary.

Neo-Calvinism and the Magisterial Reformers

It can be objected that the Neo-Calvinism of Kuyper, Orr, et al is an historical innovation. The magisterial Reformers did not appear to think or talk this way. Now I grant that they did not talk this way, but I would argue that they most certainly did think this way, at least in principle. Especially Calvin . . .

But why did it become necessary for more recent Reformed theologians to come up with the terminology of worldview thinking? As argued above, this approach insists upon the integration of all subjects with Scripture at the center. I would want to say that this became a pressing necessity as a result of the explosion of knowledge in the modern world, and the functional development of discrete “subjects.”

Our expression of “Renaissance man” comes from the time when it was still possible for a gifted man to have a handle on pretty much everything in the library. Think of somebody in the Da Vinci category. But today, over 5 million academic papers are published annually, and then there are the academic books, and after that are the thoughtful books that are well-worth reading.

When I first got married, I think I had about three linear feet of books. That number has increased since that time, and this has had repercussions. Before, I did not need a system for keeping track of them all. They were all on one shelf, right there. But now I need a system—without a system, I wouldn’t have a library, but rather a pile.

It is the same kind of thing with human knowledge. Understood rightly, worldview is a system for keeping track of everything. The need for this was not as apparent in Calvin’s day as it was in Kuyper’s, and the need is far more critical in our day than it was in Kuyper’s.

The Sinful Heart is Slippery

The sinful heart is slippery, and so of course it is possible for a man to wrap the mantle of “worldview thinking” around the shoulders of his own personal opinions, made up on the spot. Yes, that is a temptation. People can speak in the name of God when God has not spoken, and that really is bad.

But there is another temptation, far more common in our day. That is the temptation of not wanting God to have spoken at all. The lust for autonomy, even if it is a limited autonomy, is an alluring prospect for men—particularly smart ones.

Experts in psychology, or history, or physics want to have the liberty to run free in their own minds, without having to deal with the specter of their discipline ever becoming “priest-ridden.” But, as a godly grandma might say, “that’s too bad.”

Disciplines overlap. If a mathematicians went into a breakfast cafe and ordered three eggs over easy, and what he got was two eggs over easy, he might complain. And if the cook retorted that he had been slinging hash for twenty years now, and he didn’t need some pointy-headed academic to come in and tell him how to start cooking eggs. The mathematician would rightly reply that he didn’t know how to cook them, but he did know how to count them, and that at this point their disciplines overlapped.

When Carl Sagan opened up his book Cosmos with “The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be,” he was a cook failing to count the eggs right. He was not speaking in that place as a professional astronomer, but rather as an amateur philosopher, one who was making a rudimentary philosophical mistake. After the authorities reviewed the footage, it turned out that I was not encroaching in his lane, but rather that he was veering into mine.

And this kind of thing is much easier to see if you are unembarrassed by the concept of worldview. The critiques of worldview are of two kinds. One is to be rejected because it wants to give up the gains of worldview. The other makes legitimate critiques that amount to an encouragement to take it further—further up and further in.